Readings, March 3, 2019 © Scott McAndless

Exodus 34:29-35, Psalm 99:1-9, 2 Corinthians 3:12-4:2, Luke 9:28-36

| I |

have been there. There have been moments in my life when I can truly say that I went where Moses went – into the very presence of God. Oh, not literally the same place that Moses went and maybe not in the presence of God in exactly the same way but, yes, there are moments that I can point to when I had absolutely no doubt and no other way to explain it than to say that I had just experienced God. Sometimes it has happened in subtle ways that nobody would have even noticed who was around me. Sometimes it has come while interpreting scripture and when I saw a special connection or deeper understanding that I knew I could not have found by myself – the spirit of God must have been operating within me.

Other moments have been more dramatic. I will never forget the time, for example, when I was literally out of money. I didn’t tell anyone but I didn’t know how I was going to get my next meal. And yet, in that moment, I impulsively chose to make a donation of my last five dollars to a worthy offering that was being taken. It was an act of faith and trust that was perhaps foolish, but I did it. I still do not know to this day how a twenty dollar bill ended up in my mailbox the following morning. Surely God had given someone a little nudge.

And yes, of course, there have also been those moments of greatest drama when, in the midst of worship or in the midst of a crisis I just knew. Every fibre of my being just reoriented to the certainty that I was in the presence of someone far beyond my understanding.

I have experienced the presence of God. I imagine that many of you have had such moments as well. Now, since such things are personal experiences, they are usually not shared. For that reason, I cannot really use my personal experiences to prove to you that God exists. Spiritual experience is not about proof. It does, however, play an important part in the formation and forms of human religion.

The model for how that works is demonstrated in how the Book of Exodus tells us that Moses gave spiritual leadership to the people of Israel. He would go into the tabernacle – a portable sanctuary that the Israelites would carry with them – and there he would have an experience of the presence of God. What that experience was – how exactly God was there for Moses in the tent – we do not know. We cannot know because it was Moses’ own personal experience. Nobody else could share in it and you could not prove that God was there in the tent to anybody but Moses.

Nevertheless, on the basis of his own personal experience, while the afterglow of that experience was still on him and slowly fading, Moses would speak to his people and give insights and commandments to them based on what he had experienced. But, after a time, that afterglow faded, the experience became less potent in his mind, and so the time of sharing based on it would come to an end. Moses would cover his face with a veil and for a time, they would only have the wisdom given in the afterglow to fall back on until it was time for Moses to have another personal experience of God in the tabernacle.

Now, in Exodus, this is all told in quite literal fashion. Moses’ face glows with a real and frightening light which slowly fades away. He then literally covers his face with a veil during the interim time. But I would say that this is how spiritual experience always works if you set aside the literal details. Whenever a spiritual leader has a powerful experience, there is a time when he or she is able to give great wisdom and insight in the fading afterglow of that experience. But then that afterglow wisdom gets codified and even turned into law to guide the community through the period of the veil – the time when no particular guidance comes through spiritual experience.

That is how it has always worked in many faiths, not just our own. It is a fairly natural way for human beings to respond to experiences of the divine. We see the very same pattern, for example, in our gospel reading this morning. Peter, James and John go up a high mountain where they have an experience of God in Jesus Christ – a powerful experience marked, once again, by glowing white light. Peter’s response, in the fading afterglow of that powerful experience, is to want to codify it. “Let us make three dwellings,” he says, “one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” He wants to set up religious buildings where they can process the experience and turn it into commandments and regulations, just like Moses did when he came out of the tabernacle. He wants to do this so that the experience might sustain them through the long period of the veil when there is no dramatic God experience.

So that is the pattern. And it is a good pattern that human beings have developed to deal with the fact that people do sometimes have incredible spiritual experiences of God, the power of that experience fades and then we tend to go through long periods of veil time when there is no revelation. In many ways, you might say that that’s what religion is. It is the institutional structures that we build in the fading afterglow of experiences of the divine – structures that are designed to get us through the veil time.

But, while that is a natural human thing and while it is what Moses did, you probably picked up a little note in our reading from the gospel this morning – a note that seemed to indicate that Simon Peter didn’t actually respond in the right way. Jesus doesn’t say anything, but what happens immediately afterwards – the encompassing cloud, the mindless terror and the words, “This is my Son, my Chosen; listen to him!” booming from heaven, all seem to indicate that Peter didn’t quite get his response right. But what did he do wrong? What is inappropriate in what he says?

That brings us, finally, to our reading this morning from Paul’s letter to the Corinthians. In this letter, Paul is talking specifically about the very passage we’ve been discussing – about the whole description of Moses having these face-to-face experiences with God, giving laws and rules and commandments in the fading afterglow, and then putting on the veil to signify the time when that direct experience of God is completely absent. Paul understands where this comes from, but he also explains what is wrong with this model of relating to God.

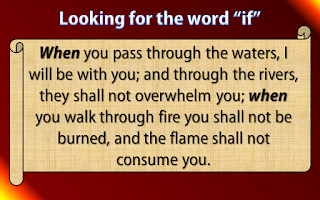

Paul writes this: “Since, then, we have such a hope, we act with great boldness, not like Moses, who put a veil over his face to keep the people of Israel from gazing at the end of the glory that was being set aside.” The problem, Paul says, is the veil. And what does the veil represent? It represents that long period of time when the direct experience of God is absent. In fact, it represents the fear of God’s continued absence. We are afraid, having had these extraordinary experiences of God at some point, that it will never happen again. And so we set ourselves up to try and make it through that long period of the veil. That is what the fading afterglow time is all about. We try to codify, to reduce the experience down to laws and rules, so that they may continue to guide us when the experience of God is absent.

The problem with all of that, from Paul’s point of view, is that it’s all motivated by fear. Having had an experience of God’s presence, we are afraid of the absence of that experience. In many ways that is the history of religion. It is the story of people who had extraordinary experiences of God and then created a religion to guide people in the absence of that experience. Now, Paul does not deny the power of those kinds of experiences. He had some of his own. They were very important and formative to him. But Paul actually resists using the fading afterglow of his experiences of the risen Christ, to give laws and rules. For him, laws and rules are the problem, not the solution.

For him, the point of whatever experience of Christ you have is not to give you rules to live by. It is to transform you. “And all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord, the Spirit.”

What, then, does all this mean? How should we apply it to the way that we live out our faith in Jesus Christ? The fact of the matter is that we are only here, we are only the church, because, at some point there were people who experienced the presence of God. It started, of course, with the apostles who, a matter of days after the death of their Lord Jesus, experienced his presence with them alive again. But they are not the only ones. The Presbyterian Church and Reformed tradition came into being because of the experiences of reformers like John Knox and John Calvin. The people who built this church did so because, in small ways and large, they had experienced God at work in their lives. The people who, down through the years, preached in this pulpit and who led in the session and in other ways in this church had their own experiences of the presence of God. None of this would have happened without such experiences.

But the temptation, Paul is saying, is to leave it at that. To take those experiences, those extraordinary experiences, and say that that is it. That the gospels were written, the church was given its structure and doctrines, this church building was erected in the fading afterglow of those extraordinary experiences. The temptation is to live out our Christian life and faith under the veil – living under the legacy left behind by those experiences. “Let’s build three dwellings,” we say with Peter, “one for the reformers, one for the people who built this beautiful church, one for the leaders who went before and that will be enough.”

To that, Paul says no. To that, Paul says, it is not enough. We must not be merely conformed to the rules and expectations of those who have gone before. We ourselves are to be transformed daily into the image of Christ Jesus – brought to a place where we don’t need those rules and expectations because we are already becoming new beings in Christ.

These spiritual experiences – our own and those of people who have gone before us – are wonderful and beautiful – but when they become the basis of religion – when we put them under the veil – they become sterile and lifeless. Paul wants us to live under a different pattern. As a daily discipline – through prayer, scripture reading, meditation and contemplation – we are to continually reflect on the very presence of Jesus among us. Our purpose is not to build dwellings, or create rules and commandments and expectations for others to follow. Our purpose is to become what we contemplate, the living Christ, moving and acting through us in the world.

Paul is calling us to something higher here – higher than religion, higher than ethics and commandments, higher than building sacred memorials to our experiences. He is calling us to become the very embodiment of Jesus in this world.