Hespeler, 23 September, 2018 © Scott McAndle

Deuteronomy 6:17-25, Mark 12:28-34, Psalm 19:7-14

A |

bout a dozen years ago, there was a United States congressman named Lynn Westmoreland who cosponsored a bill to place the Ten Commandments in the U.S. House of Representatives and in the Senate. He also had another bill that would permit the Ten Commandments to be displayed in courthouses throughout the land. That proposed legislation, and some of the things that happened as a result of it, are very interesting to me. It illustrates to me some of the ambivalence that I feel about the Ten Commandments and the Old Testament law.

On the one hand, there is absolutely no question that the laws of free, democratic countries like Canada and the United States owe a great debt to the Old Testament Law of Moses as well as other ancient law codes like the Twelve Tables of Ancient Rome and the Code of Hammurabi. For that reason, the Congress and law courts might seem to be a very good place to display such a thing.

But

Butut, of course,

But there was another very interesting thing that happened in the midst of that particular discussion. The congressman appeared on a television show called The Colbert Report where this happened;

And I am honestly not very surprised that, when Stephen Colbert asked the congressman to tell him what the Ten Commandments were, he couldn’t do it. How many of us really could? And that tells me something else about our attitude towards them. We may revere them, but it’s not really because of their contents. We revere them because of what they symbolize to us. In fact, it often seems to matter little to us what they actually say.

But I happen to believe that it is actually very important for us to know what the Ten Commandments say and what they mean. We need to treat them as more than just a symbol. This is not because I think that we need to begin to apply them directly to our modern secular society. Most of them weren’t designed for our kind of society. But as Christians, we need to understand what they are actually about. So I am glad that the upcoming section of the Catechism deals with the Ten Commandments.

But before we start to look at the individual commandments, we need to start with a more fundamental question: why are they there at all? What is their deeper purpose? Because I think that a lot of people would say that they know what the commandments are for, even if they are not quite sure what the commandments say. They are there, people assume, to keep order and make sure that people conform to expectations. They are there to curtail freedom – not in a bad way necessarily, but hopefully in a way that makes it easier for us all to all live together. Most of all, people seem to assume, the commandments are there in order to make sure that people who behave wrongly are punished.

That is how we talk about the use of the commandments and their importance. That is why lawmakers like Westmoreland want to put copies of the Ten Commandments on public display, as a way to impose order. But is that the purpose behind the commandments that we find in the scriptures? What does it say? What does Moses say when the Commandments are given? Well, the purpose of the commandments is not only given in the Book of Deuteronomy. It is given in such a way as to make sure that that purpose is not forgotten and is passed down from generation to generation.

This is what Deuteronomy reports that Moses said: “When your children ask you in time to come, ‘What is the meaning of the decrees and the statutes and the ordinances that the Lord our God has commanded you?’ then you shall say to your children, ‘We were Pharaoh’s slaves in Egypt, but the Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand.’” Moses goes on to tell the people of all that God did to save them from slavery and bring them into a Promised Land and concludes with, “‘Then the Lord commanded us to observe all these statutes, to fear the Lord our God, for our lasting good’”

When asked what the purpose of the commandments is, Moses doesn’t say “conformity.” He doesn’t say “limits on freedom” or “punishment.” He says, “Because you were once slaves.” And when you really dig into the contents of the commandments (instead of just treating them like a symbol whose contents don’t matter), I believe that you will discover that that is indeed the ideal that lies behind all of them. When you read them right, you can see that they are all about being free from slavery and especially about making sure we don’t fall back into slavery again.

Now, in weeks to come, the Catechism that has been guiding us all this year will begin to take us through the Ten Commandments one by one and we will have the opportunity to dig into the real meaning and application of some of them. Today I want us to think about how we approach them as a whole – what attitude we need to bring.

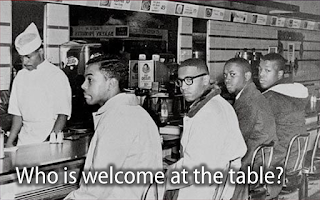

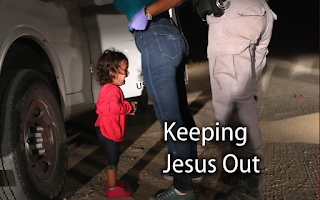

Well, the Book of Deuteronomy makes it quite easy to discover that attitude. We need to read them as former slaves. Isn’t that interesting? It suggests that people who have a direct experience of slavery – the descendants of former black slaves for example or others who have lived under circumstances where they were less than free – would probably have an easier time grasping the meaning of the commandments than most of us. That is not how we usually think about such things. For a long time, privileged people – people who can afford more education and, to be blunt, white western people – have argued that they are the ones who can best interpret the meaning of the Bible. Moses here suggests that they are not.

But, despite our handicap, despite our long experience of freedom, we need to try. We need to do our best to approach these commandments as they are supposed to be approached. So try to put yourself in that frame of mind. Imagine yourself as an ancient Hebrew, recently released (beyond all hope and expectation) from slavery in Egypt. With that in mind, how might the commandments sound different to you? Take the commandment against idols, for example: “You shall not make for yourself an idol” or, as it is sometimes translated, “a graven image.”

Well, a slave in Egypt would have been very familiar with graven images. Images of the Egyptian gods would have surrounded them on every side. But they were all the gods of their oppressors and the very fact that they were there in the physical forms of idols gave power and influence to the people who had made them and controlled their temples. The Hebrews were saved from slavery by a very different kind of God – a God who could not be reduced to the form of a statue and who would not be controlled or limited by anyone. Hmm, it makes you wonder, doesn’t it; was the prohibition against idols about protecting God’s fragile ego (like we often seem to assume) or was it more about making sure that they didn’t develop, in their new country, a class of people who could claim a monopoly on power structures? Was it about making sure that a new class of oppressors, who would create new slaves or slave-like conditions, did not arise among them?

Or what about the prohibition against “wrongful use of the name of the Lord your God,” or “taking the Lord’s name in vain,” as we sometimes put it. You know how that commandment has been traditionally used by prosperous white folks; it has been used to police and control the language of other people – most especially the language of poor folks and racial minorities. But what would a law like that mean to former slaves? Who had used the names of gods against them? Well, once again it was their oppressors. It was the Egyptians who declared that the power of their gods gave them the right to enslave others. I think that a former slave would understand that misusing the name of a god was actually about misusing that name to enslave others or to gain power over someone else in any way.

Which brings us, of course, to the Sabbath law. Once again, I think we all know how upper-class white people have tended to interpret that commandment. For them, it has tended to be a very restrictive kind of law. They have used it to put limits on all kinds of activities including on the kind of work that lower class people often have no choice but to do and on the few enjoyable activities that they can afford like dancing or playing games. Over the centuries I think that many people have experienced Sabbath laws as very restrictive things. But, let me ask you, how might a former slave who had been forced to work seven days a week since forever against their will experience a law that said you can't make anyone work seven days a week without breaks? For them, that is all about liberty. That is all about freedom and the exercise of it. Let me tell you, former slaves heard the Sabbath law in a very different way.

Now, the catechism will give us a chance to focus in on some of the commandments more tightly in the weeks to come. Let me just say that I believe that all of them are transformed when you choose to approach them as if you are presently enslaved or recently emancipated. That one understanding changes everything. For example, did you ever wonder why the Ten Commandments had two laws against theft? One says, “You shall not steal,” and the other says, “You shall not covet? What is up with that? Don’t those two laws accomplish the same thing? Well, I am sure that we will see that that does make a lot of sense if you happen to read the commandments as a former slave.

The point that I am making is that, when we approach the Bible in a way that comes most naturally to us – with all of our privileges and assumptions and priorities in place – we will draw what seems to be a perfectly obvious meaning out of it. But the Bible itself reminds you that that is not the right approach. Moses tells us to read it through the eyes of another people – through the recently enslaved. He says that only they can truly understand it. So it seems that, if we really want to understand the scriptures, it may be time to shed some of our preconceived ideas about what it means and put ourselves in the shoes of the weak, the abused and the poor. They sometimes clearly get it when we don’t.