Watch sermon video here:

Hespeler, December 7, 2025 – Second Sunday of Advent, Communion

Isaiah 11:1-10, Psalm 72:1-7, 18-19, Romans 15:4-13, Matthew 1:1-6

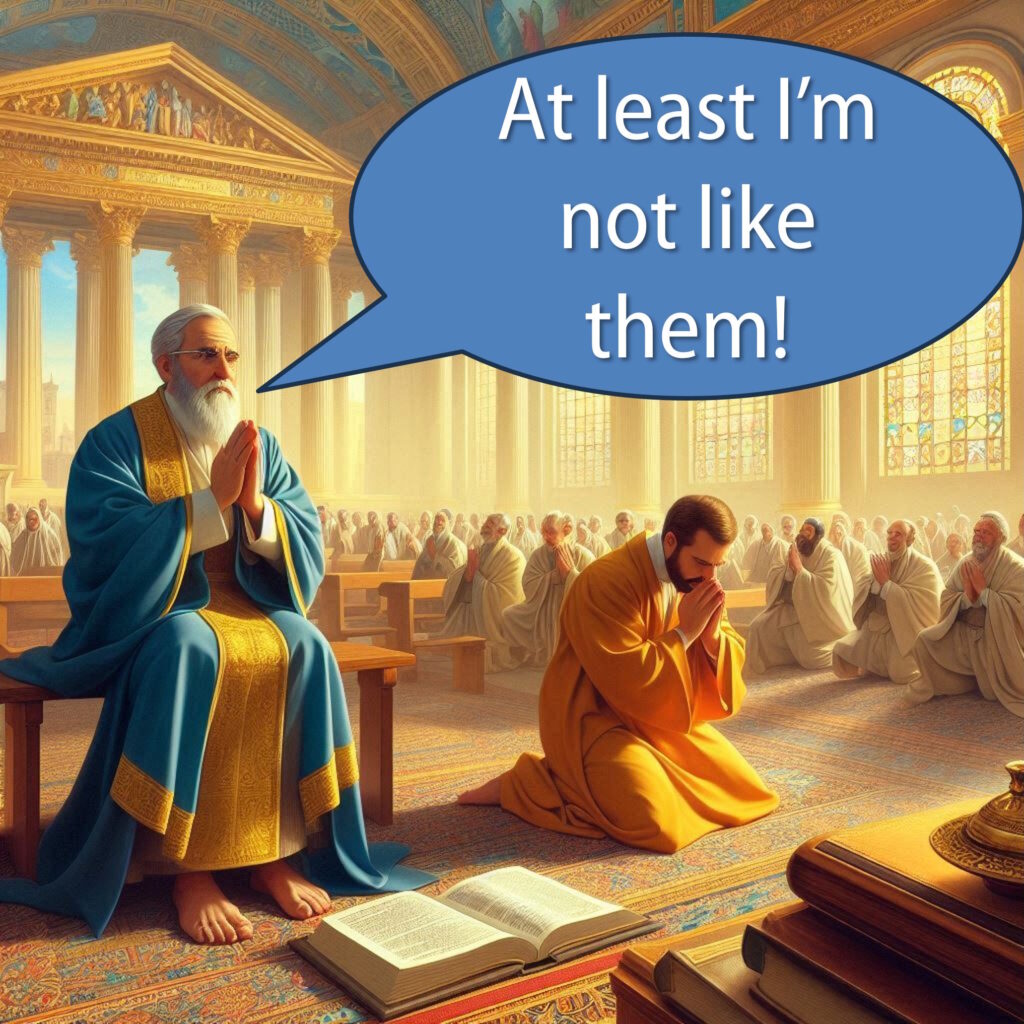

I am hardly the first person to notice this, but in his genealogy of Jesus, the author of the Gospel of Matthew includes the names of four women apart from the name of Mary, Jesus’ mother.

This unusual inclusion has raised many questions down through the centuries. Why would he mention any women? It was not normal to do so in ancient genealogies.

Why These Women?

We also have to ask why he names those women in particular? There are a few things that they have in common. They all appear to be foreigners. Tamar and Rahab were Canaanites. Ruth was a Moabite. And Bathsheba was married to a Hittite.

They also seem to all have had somewhat questionable sexual histories. Tamar and Rahab acted as prostitutes. Ruth seduced Boaz on the threshing floor. And Bathsheba was famously raped by David.

Given all of this, many have reflected down through the years on what Matthew is trying to say by including these specific women in his genealogy. And many of those reflections have brought out some of the deeper theological meanings of this Gospel.

Matthew the Storyteller

But Matthew was not just a theologian. He was also a master storyteller. So, I was thinking that maybe he didn’t just name these women to make theological points. Maybe he is going out of his way to bring them in as characters.

By opening his Gospel with a genealogy, Matthew summons all of these ancestors of Jesus to witness the story he is about to tell. They are not there as silent witnesses or theological signifiers. They are part of the story. And, with that in mind, what did these four women have to bring to the story that we are being told?

Ancestral Witnesses

Well, here are some things to think about. They are all mothers. What’s more, they are all mothers who became mothers under somewhat murky circumstances. They had to struggle to have their children, and they had to deal with disapproval by others for their struggle. They also each saved their nation in their own ways.

And yes, I think that that means that they have a great deal to say to the story that begins the gospel of Matthew, the story of a man named Joseph, who is struggling to know what to do when he finds out that the woman he is engaged to is already pregnant.

So, here’s a question for you. What would these ancestral witnesses say to Joseph in his troubled sleep as he considers what to do about Mary?

Tamar

“Dear Joseph, I am your great, great… I think maybe forty times great-grandmother Tamar. And I know you are feeling somewhat torn over the marriage that your parents have arranged with this young woman, Mary, especially since you’ve heard the rumours that she is already expecting a child that you know you had nothing to do with.

“Well, I know a few things about that whole situation, because I was in it. I had been married off to the son of Judah, Er. But Er died, and so I was given to his brother Onan. But Onan did not want to do the right thing and give me a child who would claim his brother’s inheritance, so he died too for his disobedience.

“So, there I was – a widow twice over. And did my father-in-law Judah take care of me? No, he didn’t. As far as he was concerned, I was responsible for the death of two of his sons already. He was afraid of me – afraid to give me his last remaining son for fear that he would die too.

“So, he sent me to my father’s home and left me destitute. For who would marry a woman suspected of causing the death of two husbands?

Tamar Saved the Nation

“It was bad enough that Judah had abandoned me, but he also abandoned something else – his responsibility to assure a future for his family. Because he was afraid of doing the right thing for me, he was risking the entire inheritance of his family.

“So, I had to step in to save not just myself, but to save the entire tribe (and ultimately the nation) of Judah. And yes, the way I did that was questionable to say the least. I disguised myself as a prostitute, and I did get a child off of my own father-in-law.

“And that is how I ended up in a position much like your Mary’s. I had been put into an impossible position. But I acted decisively and not just to save myself – to save the nation that would eventually come to be. I saved the future that you are now living in.

“And in the end, my father-in-law Judah had to admit that I was in the right and that he was in the wrong. So, Joseph, I guess I’m just saying that you need to look past a situation that appears bad or shameful. Don’t judge someone’s action without taking time to understand the person behind it.

Rahab

The spirit of Tamar departed from Joseph’s troubled sleep, but soon another ancestor came to speak to him. Rahab had never been a woman who had hesitated to share her feelings, and she didn’t hold back with Joseph now.

“I hear you are worried about shame, o my great, great, great, great, great, great… grandson,” she began. “Well, let me tell you something about shame. My family and I had been rejected by the people of Jericho, my city. We had been left to live in the worst place – in a house built into the great walls.

“We had lost any social supports, and so I was given no choice. If I were to be able to support my family, I would have to enter into the world’s oldest profession, which meant, of course, that I would became even more rejected and maligned.

“But I never gave up. I dreamed of a better life for my children and even to set up a rope-making operation so that they could have a respectable job.

The Power of Shame

“But the shame heaped upon us affected all of us. That’s why I know the power of shame. And it is not a good power. Far from keeping me in line, it made me rebellious. When an opportunity came to betray my city, I didn’t really hesitate.

“Oh, Joseph, shame is so very damaging. It destroys relationships and even whole cities. It never really makes anything better. You’d better think twice before you join in the chorus that would pile shame on the head of poor Mary and her child.

Ruth

After Rahab had departed, her granddaughter-in-law Ruth arrived. (Although, of course, it is possible that the Gospel of Matthew skipped a few generations, and she was a more distant descendant than that.)

“Joseph,” she began without hesitation, “it is Ruth. And as your ancestor and the great- grandmother of King David, there are a few things I think you need to know about Mary and her situation.”

Having No Support

“She is all alone now. Because of this scandal that has come up around her and this questionable pregnancy, she doesn’t really have anyone to turn to. I know exactly what that is like.

“When Naomi and I came back from Moab with both of our husbands dead and no children, we only had each other. And, yes, that woman meant the world to me. I loved her as I loved my own life, but the rules of our society were that women were not allowed to support one another.

“Joseph, I know that you’re thinking that to send Mary away quietly is the right and decent thing to do because at least it will not subject her to public scorn. However, you need to understand the world of isolation you would be sending her into.

A Helper

“Naomi and I were at our worst. We were teetering on the edge of starvation, and I had to go gleaning in the fields at harvest time – a situation where women like me were often attacked.

“We almost didn’t make it, but someone helped us. And yes, I did kind of have to go and find Boaz and he took a little bit of persuading. But he became our redeemer. And, with his help, Naomi and I and he and our son became a family together.

“But it almost didn’t happen; if no one had helped us, it wouldn’t have happened. And if it hadn’t happened, there would have been no king David, no nation of Judah, and there would not have been you lying here trying to figure out what to do about Mary. Just think about that, Joseph.

Bathsheba

There was one more visitor who came to disturb Joseph’s sleep and prepare his mind for the angelic announcement that was on its way. Her name was Bathsheba.

Now, here was an ancestor of Joseph that everyone had underestimated. Even the Gospel writer thought little enough of her that he didn’t even name her – just referred to her by her husband’s name, Uriah.

But Bathsheba had a few thoughts about that, and she didn’t hesitate to share them with Joseph.

A Survivor

“Everyone thought of me as a helpless woman,” she declared, “but I am a survivor. When David spied upon me while I was bathing in my husband’s home, when he used his high position to invade my private space, I was helpless.

“When he summoned me, I had no choice but to go to him. When he directed me into his bedchamber, I could not resist him. But I survived the devastation of that night.

“And then, when I fell pregnant, David did not care about me. He only cared about himself and his position.

David’s Failures

“In his efforts to escape accountability for his actions, he did terrible things. His destructive impulses not only fell upon poor Uriah, who had only acted with honour, but also sowed a spirit of destruction that would continue to warp David’s family and children for the rest of his life.

“The death of our firstborn child shortly after his birth, David made even that all about himself. It was all about his grief, his loss. It was as if he didn’t even realize that I had also lost a child.

“But through it all, I survived. I navigated all of the intrigues of a family that was more dysfunctional than you can imagine! And somehow, I managed to teach my second son, Solomon, to be wise enough to rise above it all.

Bathsheba Saves the Nation

“And then, when David was so old and addled that it seemed inevitable that the entire kingdom would explode into anarchy and chaos, I was ready to act again. This time, it wasn’t just about my own survival but the survival of the Kingdom of Israel itself.

“I could see it so clearly. As soon as everyone realized that David was no longer the man he had once been, a civil war would erupt, and it would destroy everything that David had built. And so I moved quickly. With the help of Nathan, I persuaded David to fulfill an old promise. He let go of his power and placed my Solomon on the throne.

“I did that – me. Not too bad for someone whom everyone had written off as a helpless woman that they could use however they wished. Never underestimate the power of a survivor. And I’ve seen this Mary of yours, Joseph; she is a survivor.

Ready for the Angel Visitor

And so, Joseph slept on. Each of his ancestors had brought a little bit of wisdom for him to consider. And that was why, when his final visitor, an angel from the heavenly court, came to bring him a message, he was prepared to receive it. He realized that he had underestimated the strength and courage that was in this woman, Mary. It turned out that she was indeed full of surprises.

Never Discount Anyone

The Gospel of Matthew says that the visit of an angel to Joseph in his dream was what persuaded him not to put Mary aside. But I can’t help but think Matthew is suggesting that Joseph could have found some strength and wisdom to create a new possibility from his extraordinary female ancestors as well.

Certainly, they, together with Mary, ought to teach all of us never to discount anyone, least of all a woman, because their circumstances have put them into what looks like a bad place.