Hespeler, 13 October, 2019 © Scott McAndless – Thanksgiving

Jeremiah 29:1-7, Psalm 66, 2 Timothy 2:8-15, Luke 17:11-19

| I |

n 2016, a young man named Colin Kaepernick, who had, up until that point, enjoyed a fantastic career in the American National Football League, made a fateful choice. Having led his team, the 49rs, to contend in one Superbowl, he was (even if his playing in subsequent seasons hadn’t taken them quite so far) on the top of his game and he could have continued to look forward to a strong and very prosperous career.

But Colin, an African American, was very upset and moved by some of the systematic problems faced by those who looked like him – the higher incarceration rates of black offenders who broke the law at the same rate as people of other races and a rash of incidents in which unarmed black men had faced unjustifiable and often deadly violence at the hands of police. Kaepernick’s life was good and he enjoyed many privileges but he felt that he had to make some public statement about the injustices that many black Americans had to deal with every day. And so, during the 2016 season, Kaepernick began, rather famously, to exercise his own personal, silent protest. He began to kneel during the playing of the American national anthem before NFL games.

As you probably know, that protest didn’t stay silent for very long. Soon not just football fans but everyone was talking about Kaepernick and his campaign. Everyone seemed to have an opinion. People accused him of disrespecting the American flag and anthem and those who have served in the armed forces despite the fact that he never spoke against such things. Some people seemed to intentionally misunderstand and misrepresent his protest. Others merely complained that, while he was legitimately concerned, he was not expressing it in the right way or at the right time. You’ve probably heard all of those things before and I don’t bring up the case of Colin Kaepernick in order to talk about such things today.

But there is one particular complaint that has been raised against Kaepernick that I feel does need to be raised here and now – in the context of a church service on Thanksgiving Day. Perhaps the number one complaint raised against Colin Kaepernick, and the one that many people have found persuasive, has had to do with his failure to be grateful. Colin Kaepernick, because of his extraordinary ability to play football, had been extremely blessed. He received a top-notch education worth hundreds of thousands of dollars on a football scholarship. As a starting quarterback, he enjoyed a top salary and benefits. He was paid so much more than the vast majority of black men in the United States, more indeed than the majority of all Americans. And yet, here he was causing nothing but problems for the NFL that paid him so well and for the country that gave him the opportunity to do so well. He should only think about all that he has as an individual and not worry about what other people don’t have. He should be more grateful, people cried.

This particular criticism of Colin Kaepernick cuts deep and on this day, of all days, it makes me question what the true nature of gratitude is and what it should be. I’m going to confess something to you here. When I saw that the lectionary reading for today, the reading from the Gospel of Luke, was the story of the healing of the ten lepers, I was a little bit distressed. You see, this is one passage but I have struggled with for years and that I especially dislike reading on Thanksgiving Sunday. It’s not really because of anything that’s actually in the story. It’s a wonderful story of healing and hope and grace as Jesus reaches out in it to some of the most disadvantaged and despised people in his society. No, my problem with it is how it has often been used on this day. In my experience, it has been used by privileged people to coerce gratefulness from those that they seek to control.

It starts young and often with very good intentions. I have often seen this story used as a way to teach people – especially young people – of the importance of expressing thanks. The hero of this story of Jesus, we are told, is the one leper who alone out of the group, returns and kneels down to say thank you for what Jesus has done for him.

The lesson, often the only lesson that some people get out of it, is that that you should always say thank you. Now, on one level, I am all for that. It is good to express your thanks and the world would likely be a better place if people did that more often. I am glad if children are taught to have that as a habit. My wish for all of us on this Thanksgiving Day is that we learn to celebrate and be grateful for what we have for there is so much contentment be found in that basic attitude.

But there are moments when people’s expectation of gratitude from others becomes a problem. Think of the expectations that are often put upon racial minorities in North America. Yes, they do have much to be grateful for to be living in a country with so much prosperity and so many better opportunities then they likely would have had in their countries of origin. They are grateful. But does that mean that they cannot criticize incidences of racism or prejudice or systems that are biased against them having a fair chance? Because that is what they are often told.

Most colonized people, including Canada’s own indigenous people, face the same expectations. They should be grateful, they are constantly reminded, for the benefits of modern Western civilization that they enjoy – education, medicine, infrastructure and more – but the underlying message behind that expectation is often that they shouldn’t lament the culture or language they may have lost, they shouldn’t lament the loss of the indigenous lifestyle or family structure or political independence that they have lost. Above all, the underlying message always seems to be, being grateful means that they should not disturb us with their complaints or demands. But is that truly what gratefulness means?

In our reading this morning from the Book of Jeremiah, we find the prophet writing to a group of people called exiles in Babylon. These are people who have been ripped from their homes and been forced to travel for months and relocate in a land far from home. They are not immigrants; they are not refugees; they are exiles. Perhaps the closest thing that we can relate to is to say that they were kind of like the African Americans who, generations ago, were taken from their homes and relocated to North America as slaves against their will.

So Jeremiah writes to these people. And I think he wants them to feel a bit better about where they are. And, honestly, there were some good things about being in Babylon. There was culture, the greatest culture on the face of the earth at the time, there was learning and infrastructure that ancient Israel simply couldn’t compete with. Why they apparently had hanging gardens in Babylon – one of the ten wonders of the world! They did have a chance at building a good life there.

So, you know what, Jeremiah probably could have written to them and told them that they should be grateful for all the good things they had and forget about all the bad stuff. But I notice that he didn’t do that. Yes, he does tell them to stop putting their lives on hold and start building something where they are. “Build houses and live in them; plant gardens and eat what they produce. Take wives and have sons and daughters; take wives for your sons, and give your daughters in marriage, that they may bear sons and daughters; multiply there, and do not decrease.”

That is, by the way, some pretty good advice. When things go wrong, when things don’t quite work out according to what we imagined, the temptation is always to put your life on hold and blame your situation for everything that you don’t like about your life. But nobody gets anywhere that way. Whatever your circumstance, whatever has gone wrong, your first order of business is to find a way to get on with your life. That is, in fact, a kind of gratefulness. It means not getting caught by the negatives, or at least not letting them stop you from moving on with your life.

That is a good attitude, but it doesn’t take away from whatever injustices or indignities you may have suffered. And, in fact, it may well mean that you are working on rebuilding your life in defiance of those who have oppressed you.

Jeremiah is not done. He has one more very important piece of advice for the Judeans in exile: “seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.”

And I know how that might sound. It might sound like Jeremiah is telling them what hateful people sometimes tell immigrants and refugees. Some might interpret that to mean that they should just become Babylonians and forget who they have been. But I don’t think that that is what he’s saying. They are to take everything that they are and the God that they serve and use it to seek the welfare of the place where they have been taken. That includes seeking to make it a better place – a better place for all people, even for the exiles who are there. And some of the Babylonians might not appreciate all of the things that the exiles think would bring the welfare of the city. It’s about communication and compromise. It’s about everyone building the welfare of the city together and everyone bringing everything they’ve got to that process.

I am grateful for this incredible country in which I live and which I love. I am grateful for the many and diverse people who come from many different backgrounds and bring an incredible richness to this country. But being grateful for this country does not merely mean but I’m going to build my own life and live it out as best as I can. That would be a very self-centred kind of gratitude. I will seek the welfare of this place where my God has placed me. Because I’m grateful for it, I will do what I can to make it better, to more fully reflect God’s intentions for all peoples. And that might disturb some people, because it gets in the way of how they thought they were going to build their life.

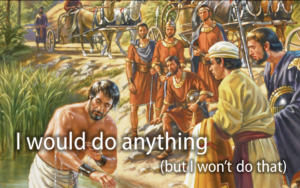

I guess what I’m saying is that, on this Thanksgiving Day, I am struck by the image of not one but two kneeling men. One kneels at the feet of Jesus in gratitude because Jesus has healed him and set him free and restored him to human society. The kneeling is a show of respect and honour for Jesus and the God who sent him. And, yes, he can and should inspire us to be truly thankful for all that we have received from God’s hand.

The other man also kneels. He kneels in honour and respect though some do not see it that way. He kneels because he is truly grateful for all that he has received. But he also kneels in protest because his country is not everything he believes that it should be. And I know that there are lots of people who don’t like that. You may not like it. That is fine; you’re not supposed to like it. That is kind of the point of protest after all. But I would like you to at least consider that sometimes, the true spirit of thanksgiving means more than silent gratitude for the situation in which you find yourself. It means that you have to seek the welfare of the city in which God has placed you – the welfare of all who live there, even those who may not have the voice that you have.

This Thanksgiving will you kneel in true gratitude?