Hespeler, 27 January, 2019 © Scott McAndless

Nehemiah 8:1-3, 5-6, 8-10; Psalm 44:1-26; Luke 4:14-21

n the Gospel of Mark, there is a story of Jesus’ visit to his own hometown of Nazareth. Jesus, who has already established himself in other places throughout Galilee, goes home and he speaks in the local village gathering or synagogue. But the people in Nazareth reject him saying, “Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon, and are not his sisters here with us?” (Mark 6:3) Their reaction seems to indicate that they think they know Jesus too well and so are not willing to accept the authority that he is claiming for himself.

What we don’t get in Mark, however, is an actual account of what Jesus said to inspire such offense. For that you need to turn to this morning’s reading from the Gospel of Luke. And what you find there is a little bit surprising. You see, I know, having read the Gospel of Mark, that the people in Nazareth are going to be upset with Jesus. So, as I read through Luke’s account, I keep expecting the outrage to occur, but it just doesn’t happen when I think it’s going to happen.

It goes down like this: Jesus comes to the gathering and participates in it by reading from the scriptures. This mig ht seem a little bit presumptuous for a hometown boy who has developed a bit of a reputation to be reading to his town elders, but you can hardly expect anyone to object to someone sharing the revered scriptures and of course nobody does.

Next Jesus sits down, which was the traditional position of a teacher in that culture and that signals that the next thing that he will say will be his own teaching or interpretation of what he has just read. So this is it, right? Surely the people are going to be offended that this Jesus, this boy that they have known from childhood, is going to presume to teach them something about the scriptures. That is what the account from the Gospel of Mark has set us up to think. And yet, it would seem, according to the Gospel of Luke, the people do not have a negative reaction and they seem to receive it well. “The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him,” Luke says.

So what then is the offence? Well, perhaps it is what Jesus actually has to teach them. “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing,” Jesus says. Okay, now he is going to get it. Surely the good people of Nazareth are not going to accept hearing such a thing from Jesus! Basically, he seems to have just announced that, because he is on the scene, the ancient scriptures have been fulfilled – in effect that he himself is the fulfillment of scripture. You could even understand Jesus to be announcing to the people of his hometown that he is the long-awaited Messiah. This, surely, they are not going to accept; they will be outraged at his presumption. Come on, they knew this guy when he was still in diapers!

But no, amazingly that is not their reaction at all. In fact, they seem to be quite astounded, but in a good way. “All spoke well of him and were amazed at the gracious words that came from his mouth. They said, ‘Is not this Joseph’s son?’” So clearly (and despite what Mark implied) the issue that the people have with Jesus is not merely that they think that he is too big for his britches.

So, what is it? What sets them off? What gets them so mad, in fact, that by the end of our reading they are ready to throw him off the nearest cliff? It is one thing alone. Jesus just happens to mention that God’s grace and salvation might be made available to other people – people who are different from the people in Nazareth – Gentiles. He talks about a widow who was saved by the Prophet Elijah and an army commander who was saved by the Prophet Elisha, both of whom just happened to be Gentiles. He dares to point out to them that there were times when God loved and saved people who weren’t like them – people that they despised. That was what was enough to send the people of Nazareth into a murderous rage.

Today’s sermon is a little bit different. As you know, since the beginning of the year I have been using the lectionary to guide me in my preaching. The lectionary, by the way, would have directed me to read only the first half of that passage from the Gospel of Luke. But last fall I put up today’s sermon in the auction – the winning bidder would be able to dictate the topic of today’s sermon and Joanne Waugh had the winning bid. She has asked me to answer the question, “why is it that we have so much trouble dealing with change in the church.”

I’m sure that you’ve all heard the old riddle, “How many Presbyterians does it take to change a lightbulb?” The answer, of course, is that the old light bulb worked just fine back in the 1960s, why would you even think about changing it?

It is true that change in general is difficult for the church, but I think that Joanne in her question recognizes that there are certain kinds of change that are a little bit easier than others. And it is kind of surprising the kinds of change we can tolerate.

The people in Nazareth don’t seem to have too many problems with many of the radical things that Jesus says to them. They seem to take the suggestion that “the year of the Lord’s favour” has arrived and the notion that the scriptures have been fulfilled without surprise. Even the idea that this Jesus, this man they have known since childhood, could be God’s Messiah doesn’t really seem to faze them. But the change they find to be particularly troubling and that they really can’t handle – so much so that they try to shove Jesus off a cliff – is the idea that God might choose to show grace and salvation to the wrong sorts of people in their estimation.

And I think it works the same way with us. We may disagree on certain matters of theology. You may not, for example, conceive of the Holy Trinity in exactly the same way that I do. We seem to be able to tolerate those kinds of differences without too much trouble. The disagreements that really tear us apart tend to be those disagreements about who is in and who is out. The things that get us all worked up are the questions about extending God’s grace to people who don’t seem to belong as far as we are concerned. Clearly the big question in the early years of the church had to do with whether the Gentiles were in or out. The particular in and out groups have changed over the centuries. Today our fights tend to be over how to include very different groups and how God’s grace extends to them – the biggest one today being the LGBTQ question. But whatever particular group you are talking about, it remains a question that we battle over with the greatest intensity.

Now, Joanne is not really asking me to tell you who should be the in group and who should be excluded from the church in our present time. What she is asking is simply why these kinds of questions are so difficult for us, why they make us want to throw people off a cliff. And she wants to know how we can approach those kinds of questions in a better way – a way that is perhaps based less on emotion and fear than on thought and a spirit willing to listen to God. The good news is that I think there is a way.

You probably noticed that we haven’t yet done our responsive reading this morning. That is because I was saving it until this time because I think it is a part of the answer to Joanne’s question. Our reading is taken from Psalm 44 this morning and so let’s pause now for a moment and read it together.

Responsive Reading: Psalm 44:1-26

L: We have heard with our ears, O God, our ancestors have told us, what deeds you performed in their days, in the days of old:

P: you with your own hand drove out the nations,

L: but them you planted;

P: you afflicted the peoples, but them you set free; for not by their own sword did they win the land,

L: nor did their own arm give them victory;

P: but your right hand, and your arm, and the light of your countenance, for you delighted in them.

L: You are my King and my God; you command victories for Jacob.

P: Through you we push down our foes; through your name we tread down our assailants.

L: For not in my bow do I trust, nor can my sword save me.

P: But you have saved us from our foes, and have put to confusion those who hate us. In God we have boasted continually, and we will give thanks to your name forever. Selah

L: Yet you have rejected us and abased us, and have not gone out with our armies. You made us turn back from the foe, and our enemies have gotten spoil.

P: You have made us like sheep for slaughter, and have scattered us among the nations. You have sold your people for a trifle, demanding no high price for them.

L: You have made us the taunt of our neighbors, the derision and scorn of those around us. You have made us a byword among the nations, a laughingstock among the peoples.

P: All day long my disgrace is before me, and shame has covered my face at the words of the taunters and revilers, at the sight of the enemy and the avenger.

L: All this has come upon us, yet we have not forgotten you, or been false to your covenant.

P: Our heart has not turned back, nor have our steps departed from your way, 19 yet you have broken us in the haunt of jackals, and covered us with deep darkness.

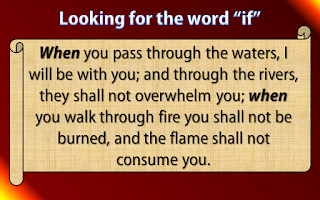

L: If we had forgotten the name of our God, or spread out our hands to a strange god, would not God discover this?

For he knows the secrets of the heart. Because of you we are being killed all day long, and accounted as sheep for the slaughter.

L: Rouse yourself! Why do you sleep, O Lord?

P: Awake, do not cast us off forever!

L: Why do you hide your face?

P: Why do you forget our affliction and oppression?

L: For we sink down to the dust; our bodies cling to the ground.

P: Rise up, come to our help. Redeem us for the sake of your steadfast love.

Now, please take a moment to consider that psalm. It is a collective prayer – the whole people have come together to pray to God – something that we still do when we gather. But it is a prayer unlike anything I have heard in a church. What do the people say to God? I would summarize the prayer basically like this: “God,” the people say, “do you remember the good old days? Things used to be so good. You used to do such great things back then.” Actually, that does sound a lot like what I hear in lots of churches – I just don’t hear people say it in prayer. “But there is a problem,” the prayer goes on. “Things aren’t so good anymore.” And it goes on from there to blame God and complain about how God is generally not doing a very job at being the God of Israel. And that is about it. It is nothing more and nothing less than a prayer of complaint against God.

This is a kind of prayer that shows up quite frequently in the Bible. It is called a psalm of communal lament and it is essentially that: a prayer for a community that is angry with God and is not afraid to say so. It is actually rather shocking for many Christians to realize that this kind of prayer is found in the Bible. We are usually taught that you should never complain – never say anything negative about God – but the people in the Bible did it all the time.

And I think that were wiser than us in that. Sometimes lament and complaint is exactly what you need to do. Sometimes you just cannot get over a loss, a disappointment or a grief without finding some concrete way of expressing your anger. And when you do it in prayer, it can be the most helpful and healing way to do it. You don’t hurt anybody’s feelings but God’s and, believe me, God can handle it.

And I think that there is a helpful answer to Joanne’s difficult question in that: Why do we struggle to see God’s grace extended to new people – people who are not like us? The reason is that, when other people experience God’s grace, it feels like we are losing out, like we are not so special anymore. It feels like a loss of privilege. We were comfortable with the idea that God could love and save good Presbyterians who thought exactly like us. But it feels like a betrayal when we learn that God might love people who approach faith in a completely different way from us.

We’re mad – mad at God – that God might choose to love and save such people. But, as good modern Western Christians, we would never think to say it. That would be wrong – maybe sinful. My feeling is that we ought to learn something from the Biblical writers and really let God have it – tell God how we really feel. Maybe it could be the beginning of us opening up to something new.

I actually do believe that God is calling new people to salvation and hope in Christ. He must be, because it was always a part of God’s plan to draw multitudes into the great work of the church. And there just aren’t so many people who are just like us anymore. If there is going to be growth, it’s going to have to come from the outsiders – people not like us. That means change – change that will likely feel like it hurts and that feels like a loss to us. We cannot afford to get stuck in that grief and loss though. So I believe that the first thing we’re going to have to do is tell God how it really feels to lose what we thought was our special status and favour.

So let God know how you feel. God, I’m mad that the methods of building up the church in the past don’t work anymore. I’m mad that, if we are going to attract new people into the church, we’re going to have to let them make changes. It’s not fair, God. This is my church, how can you let them define it! Don’t be afraid to let God know – it is one of the gracious ways in which God will allow you to embrace newness and change.