Hespeler, 1 April, 2018 © Scott McAndless – Easter

Luke 24:1-6a

T |

he sun was rising on a new day, but it was also rising on a new reality. There, inside a borrowed tomb, had been a man utterly defeated. He had stood up against the greatest powers in this world – the power of hate, the power of privilege and exploitation, the power of death – and he had been defeated in the worst and most shameful way possible. The dark powers of this world had won as they always seem to win.

But on that Sunday morning, all of that had been changed. Defeat had been turned into victory. Shame had been turned into glory. And, in that place haunted by the regrets of what might have been, death had been turned into life.

I wonder if we understand what this really means. It means that the fighting is over – that the battle is won once and for all. The greatest and most persistent powers of this world have been routed. And I have long wondered, if the greatest dark powers of this world were defeated way back then, why is it that so many still to this very day are living in a world of shame, discouragement and death?

But those women aren’t the only ones. You still do that, don’t you? You seek the living among the dead. Don’t be surprised that I know your secret; I only know it because it is my secret too. We look for the things that give us life among the dead things of this world. Many seem to assume that wealth and possessions can give us life but these things are dead. How can they give life?

Some people live only for the pleasures of the body – no matter what those pleasures may be. The lusts of the flesh take many forms. And it is a good thing to enjoy these things – good food, pleasurable experiences, that feeling when you are strong or powerful – but remember that your body and the pleasures that it experiences are mortal and limited. When you live only for these things, you are spending your life pursuing what is ultimately dead. Is that not also a case of seeking the living among the dead?

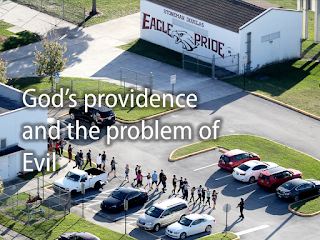

No, we are not called to seek the living among the dead. As followers of Christ, the risen one, our job is to spend our lives for the sake of what is alive. Our job is not to perpetuate the ways of death – the philosophy that says that the only way to deal with the violence and killing of this world is with more killing and violence – our job is to show the way of life.

One way that we do that is by proclaiming, as we do on this day, that the tomb is empty, that Jesus is risen and that we have come to know him even though he did die. One way that we do that is by proclaiming that the power of violence and death have been defeated once and for all, that they are false lords sitting on empty thrones. One way that we do that is by gathering at this table where we celebrate a meal that is not merely eaten in memory of a great man who sadly died but is the feast of the living Christ.

When we eat and drink in hope at this table, we can know that he is alive and present with us in this moment and will continue with us as we leave this place even as these morsels of bread and sips of wine will go with us and remain part of us. He will be with us always, even until the end of the age.

Why do you look for the living among the dead? It is a good question. You don’t need to. He is alive. He is present and I invite you now to join together in the feast celebrating that new reality.

Hespeler, 1 April, 2018 © Scott McAndless – Easter

Luke 24:1-6a

T |

he sun was rising on a new day, but it was also rising on a new reality. There, inside a borrowed tomb, had been a man utterly defeated. He had stood up against the greatest powers in this world – the power of hate, the power of privilege and exploitation, the power of death – and he had been defeated in the worst and most shameful way possible. The dark powers of this world had won as they always seem to win.

But on that Sunday morning, all of that had been changed. Defeat had been turned into victory. Shame had been turned into glory. And, in that place haunted by the regrets of what might have been, death had been turned into life.

I wonder if we understand what this really means. It means that the fighting is over – that the battle is won once and for all. The greatest and most persistent powers of this world have been routed. And I have long wondered, if the greatest dark powers of this world were defeated way back then, why is it that so many still to this very day are living in a world of shame, discouragement and death?

But those women aren’t the only ones. You still do that, don’t you? You seek the living among the dead. Don’t be surprised that I know your secret; I only know it because it is my secret too. We look for the things that give us life among the dead things of this world. Many seem to assume that wealth and possessions can give us life but these things are dead. How can they give life?

Some people live only for the pleasures of the body – no matter what those pleasures may be. The lusts of the flesh take many forms. And it is a good thing to enjoy these things – good food, pleasurable experiences, that feeling when you are strong or powerful – but remember that your body and the pleasures that it experiences are mortal and limited. When you live only for these things, you are spending your life pursuing what is ultimately dead. Is that not also a case of seeking the living among the dead?

No, we are not called to seek the living among the dead. As followers of Christ, the risen one, our job is to spend our lives for the sake of what is alive. Our job is not to perpetuate the ways of death – the philosophy that says that the only way to deal with the violence and killing of this world is with more killing and violence – our job is to show the way of life.

One way that we do that is by proclaiming, as we do on this day, that the tomb is empty, that Jesus is risen and that we have come to know him even though he did die. One way that we do that is by proclaiming that the power of violence and death have been defeated once and for all, that they are false lords sitting on empty thrones. One way that we do that is by gathering at this table where we celebrate a meal that is not merely eaten in memory of a great man who sadly died but is the feast of the living Christ.

When we eat and drink in hope at this table, we can know that he is alive and present with us in this moment and will continue with us as we leave this place even as these morsels of bread and sips of wine will go with us and remain part of us. He will be with us always, even until the end of the age.

Why do you look for the living among the dead? It is a good question. You don’t need to. He is alive. He is present and I invite you now to join together in the feast celebrating that new reality.