The Boy in the Temple

Hespeler, December 29, 2024 © Scott McAndless – First Sunday after Christmas Day

1 Samuel 2:18-20, 26, Psalm 148, Colossians 3:12-17, Luke 2:41-52

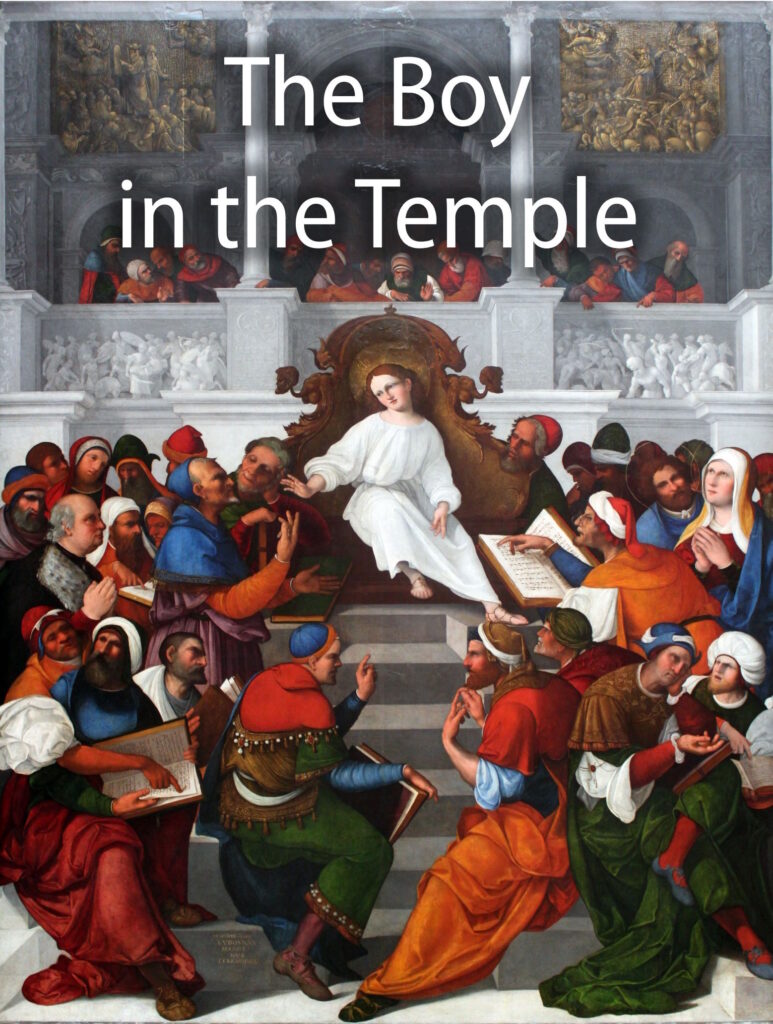

There are certain scenes from the Bible that have been depicted in art over and over again down through the centuries. The crucifixion, the annunciation to Mary, the sacrifice of Isaac are biblical episodes that artists have turned to again and again, seeking to explain and interpret the meaning of these amazing stories through the medium of art.

And one of those scenes that has been depicted like that comes from our reading this morning in the Gospel of Luke. There is something about that idea of the young Jesus talking with the scribes and teachers in the temple that artists just haven’t been able to resist. Again and again, they have taken up their brushes to try and show us what they think it looked like.

And so, I went on Google to do a bit of a survey of the history of the depiction of this scene. And I’ve got to say that I found it all very interesting. So many of the pictures had much in common. But let me show you one picture that stood out to me because it incorporates all of the key elements. It was painted by Ludovico Mazzolino sometime around 1524 in Northern Italy.

Ludovico’s Version

Let me point out a few details that are very common. First of all, and most important of all, your eye is immediately drawn to the central figure, the young boy Jesus. He is dressed in pure white and bathed in light. Everything else is in relative darkness. This Middle Eastern child also looks surprisingly white and European, but of course that is a common feature in most Western art depictions of Jesus!

And then there is the expression on his face. Jesus is perfectly serene. He is clearly self-assured and is making a firm “talk to the hand” gesture towards someone who is arguing with him that seems to say, “You poor man, you don’t understand anything, do you?”

The Faces Around Jesus

Meanwhile, look at the expressions on the faces of the people around him. Their faces (which are, by the way, all stereotypically Jewish) reflect only confusion, annoyance and anger. There are, three exceptions, though. On the right of Jesus, we see his parents, Mary and Joseph, approaching. Mary also looks very white and is in an attitude of adoration while Joseph (who I guess is allowed to look Jewish) seems to be staring at Mary trying to figure out what she is thinking.

And then there is another puzzling figure on the left. This balding man also looks European and is an attitude of pure devotion. Who is he? Well, it turns out that we know exactly who he is. His name is Francesco Caprara and he is the guy who paid for the painting. I hope he paid well to be immortalized for all time!

But I don’t share this picture with you as a lesson in art history. I think it gives us a great deal of insight into how people have read and interpreted this story down through the ages and right up to today. There are all kinds of theological ideas and assumptions that we bring to this story that are reflected in it.

Theological Assumptions

For example, we all know who Jesus is supposed to be – that he is God incarnate. And so, the assumption in this picture seems to be that, even if he is only twelve years old, Jesus already has everything figured out. Nobody needs to teach him anything. He already has all the answers. Most of all, Jesus is literally above everyone else when it comes to understanding.

There are also, to be frank, a few antisemitic assumptions at work in the picture. It sees Judaism as a possibly false religion of anger and confusion that Jesus has come to supplant. The Jewish teachers who appear in the picture are not very attractive. The message seems to be that Christians have all the answers and they understand nothing. The message is Christians good, Jews bad.

And all of those assumptions that are there in that painting are part of the baggage of the Christian faith that many of us still carry with us to this very day. The idea that the Christian faith has somehow superseded the ancient faith of Israel is very common, even though the church officially rejects that as a heretical notion.

He Already Knew

But it is the other assumption that I particularly want to focus in on today – the notion that, when the twelve-year-old Jesus was in the temple, he already knew all of the answers. No one had anything to teach him. In fact, he must have been there to teach the Jewish teachers and set them all straight.

I understand where this kind of thinking comes from, of course. If, as we often confess, Jesus really is, in any sense, God living among us, then surely Jesus came into this world with the full knowledge of, well, everything that God knows. The conclusion, therefore, that nobody could presume to teach Jesus anything seems obvious.

We’ll get to the question of whether that is really how Jesus is portrayed in the gospels in a moment, but let us first reflect on how that assumption affects us in our Christian lives.

The Example of Jesus

Jesus, is after all, our perfect example of faith. Because of this, many seem to assume that the supreme proof that they have faith is that they never have doubts. They never question what the Bible says and that no one can change their mind about what they believe. Have you known people like that? I have.

I remember once, when I was quite young coming to what I thought was an amazing realization. I suddenly decided that I knew how to be right all the time. All I had to do was find a quote in the Bible – something that declared a simple truth – and I could know that whenever I said that I would be right.

I Got Wiser

Now, I grew out of that notion fairly quickly. I had not asked if we are even supposed to read the Bible as literally true all the time or if there might be other kinds of truth. I had not considered things like whether words might have had different meanings in their original language and context or whether what the Bible said in one place could be contradicted someplace else.

As I grew older and wiser, I discovered that the more I read the Bible, less I knew for sure. The more I studied, the more I realized that I had to learn. But the thing is that many do not grow out of my early childish assumption. They think that the only way to show that they are people of faith is to never express any doubt or ask any question.

Self-Assured Christians

For them, being a good Christian means that you are always self assured. Like Jesus in the painting, their only response to anything other than what they have already decided is true is, “talk to the hand.”

But all this time I have been talking about how this episode in the Gospel of Luke has been portrayed and what people think it means. I think it might be time to consider what the passage actually says. Does it say that Jesus already had all the answers or that he had gone there to set all the Jews straight? Well, let’s take a look at the text.

What the Text Says

We are told that, when Mary and Joseph left Jerusalem traveling, we must imagine, with a large party from their hometown, they traveled for a whole day without realizing that Jesus wasn’t with them. They then turned around and went back – another whole day of traveling – and searched the entire city for him for three days.

So, Jesus has been missing for five days in the big city. I don’t even want to think of all the horrible things that his parents might have imagined happening to him. And what has he been doing for five days? Well, it seems that he has spent all of that time “in the temple, sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions.”

He didn’t Have it Figured Out

And that, to be clear, is not what Jesus is pictured doing in my favourite piece of art. The Gospel of Luke doesn’t say that Jesus already had it all figured out. It doesn’t say that he had all the answers and had been busy for five days teaching the Jewish leaders. On the contrary, he seems to have decided that he has a lot to learn and so, on the fifth day, he is still listening and asking questions.

I realize that people might be confused by the next verse where it says, “And all who heard him were amazed at his understanding and his answers.” You might take that as saying that Jesus was answering their questions because he understood better than any of them.

But the word “answers” can also be translated as “his responses.” And since Luke has already told us that Jesus was the one asking the questions, what he seems to be saying is that Jesus was responding to their teachings with questions that were so insightful that they were amazed at his understanding.

Questions

Makes you wonder, doesn’t it? What kind of questions was Jesus asking? I mean, I think I could come up with a few.

“When it says the God created light on the first day and the sun, moon and stars on the fourth, where was the light coming from for those first three days? When God stopped the sun in the sky for Joshua why, since the sun doesn’t actually move and it only looks that way because the earth is rotating, didn’t everyone go flying off the face of the earth due to centripetal force? How on earth does a Twelve-Year-Old child survive for five days in a big city with no food and no place to sleep?”

I mean, those are a few questions that come to my mind but I’m sure that, if everyone was amazed at his understanding, Jesus’ questions must have been much more insightful than anything I can come up with. But my point is that you can’t ask questions like that without wondering, without expressing a bit of skepticism or doubt. Intelligent questions can only come out of minds that are open enough to consider all possibilities.

God Incarnate

And that means that when we confess that Jesus was God incarnate, whatever that means, there has to be enough space in what we are saying for the twelve-year-old Jesus to not have all the answers – to not have it all figured out and to be in a position where he’s truly questioning everything.

And, while that is something that may challenge the way we’ve always seen Jesus and the Trinity, it also needs to challenge something else. It needs to challenge the ways in which we think of what it means to be faithful Christians.

The notion that many people have that being a good Christian means that you never question and never doubt is very unhelpful. It leads people to suppress things like critical thinking and discussion. It leads them to treat those who express an alternate view or who struggle with teaching as dangerous adversaries when they should be friends and allies. It encourages a kind of Christian life that is defined by judgement and a false air of self-assurance that frankly turns people off.

Christology

The Christian doctrine of the Christ (which is called “Christology” if you ever want to impress people at parties) teaches that, while he was fully divine, Jesus was also fully human. And true humanity does not exist without the experience of questions and doubt and critical thinking. These things make us human.

If you want to follow in the path of Christ, you will not succeed by suppressing what makes you human. That is why I would indeed hold up the story of the young Jesus as an example – not the story as it lives in our imagination and our art, but the way that the story is actually told in the gospel.

Christmas Eve Service

Voices of Christmas

Longest Night Service

Zechariah, the Righteous Priest

Hespeler, December 08, 2024 © Second Sunday of Advent

Luke 1:5-14, Malachi 3:1-4, Luke 1:68-79, Philippians 1:3-11,

If you read the story of the birth of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, you will find that one of the most important characters in that story is a king named Herod the Great. He is the one who meets the Magi when they arrive in Jerusalem searching for a newborn king. He calls together the priests and scribes to answer their question as to where the Messiah should be born.

Herod is also the one who asks the Magi to come back to him and tell him where the child is and, when they don’t come back, decides to send his soldiers to Bethlehem and kill all of the young children there for fear that this Messiah might take his kingdom.

And since, by the way, we know that Herod the Great died around 4 BC, that gives us a pretty clear date for the birth of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew. Jesus must have been born sometime before 4 “Before Christ,” which I know messes with our calendar no end, but there you have it.

Matthew vs. Luke’s Nativity

Herod the Great is all over the story of the birth of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew. He is the great malevolent presence, the villain whose villainy moves the plot forward. The story wouldn’t work without him.

Imagine my surprise therefore when I flip over to the nativity story in the Gospel of Luke. Where is Herod the Great in that story? Nowhere! Far from being the main antagonist, he is completely absent. The chief villains are instead Roman officials like Caesar Augustus and the Governor Quirinius.

One Small Note

But there is one small note at the very beginning of the Gospel. As the Gospel story opens, there is a description of the father of John the Baptist. “In the days of King Herod of Judea,” it says, “there was a priest named Zechariah, who belonged to the priestly order of Abijah.”

Now, there are actually a few “King Herods” in the Bible, but that seems to be a reference to the one known as Herod the Great. Many scholars take that as an indication that, despite the fact that Herod plays no role in Luke’s story of the birth of Jesus, the Gospel of Luke agrees with Matthew that Jesus was born before King Herod died.

But I am not so sure. I think that there is actually a whole lot more going on in those few words of introduction than that. I think that there is a whole story being told in those few words and I’d like to try and tell that story to you.

Herod and the Priests

Zechariah would never forget the day when he was ordained as a priest of the Lord. It had happened in the days when Herod was king over all Judea. And that was the source of so much scandal. Herod thought that, as king, he got to decide who served as High Priest. For example, he once removed one High Priest and installed another who was the brother of his wife. Then, when that High Priest wasn’t loyal enough, he had him murdered within the year!

And that was just one example of Herod’s meddling with the priesthood. Unsurprisingly, his blatant nepotism and use of the priesthood as a tool of his own political interest only lowered the esteem of the temple in the eyes of the populace. How could such a corrupt and dysfunctional institution possibly mediate the relationship between the people and their God?

Worthy Priests

And that is what made his own position so meaningful to Zechariah. He was not a High Priest, of course. His position was so lowly that Herod was probably not even aware that he existed. Zechariah gained his position because God (and not the king) had chosen his family as one of twenty-four to serve in the temple.

What’s more, Zechariah’s wife, Elizabeth, was descended from none other than the OG High Priest, Aaron himself! She had more of a claim to the high priesthood in her little finger than any of Herod’s choices had in their whole bodies – or at least she would have if she were a man.

And so, though he was nothing more than a small cog in a temple institution that seemed completely corrupt, Zechariah decided that he was going to be the one to make a difference. He vowed that both he and Elizabeth would be righteous before God, living blamelessly according to all the commandments and regulations of the Lord. That, if nothing else, would set him apart from the complete mess that had overtaken the temple “in the days of King Herod of Judea.”

Zechariah did this because he knew that it was the right thing to do. He did it to go against a culture of corruption and self-interest that had overtaken the temple. The only question was whether God would notice. Would the faithfulness of Zechariah be enough to trigger the salvation that the nation needed?

Fruitless Service

As the years went by, the answer to that question increasingly seemed to be no. Zechariah did his best. God had chosen him to serve in the temple – and, yes, he did believe that when he was chosen by lot it was God making a choice, calling him to serve by name. Zechariah knew that his very existence as a priest made him a living challenge to King Herod who thought that he got to decide who could serve God.

Season after season, Zechariah did his best to serve with integrity. He maintained the noble traditions of worship of the Lord and resisted the lure of wealth and power that led the chief priests astray. He quietly did what needed to be done, interceding for the people with constant rituals of prayer and doing what he could to communicate God’s grace to the people.

But it all seemed to have no effect. All the people could see was the corruption of the temple – a rot that had set in from the top but that seemed to have permeated it through and through. They began to avoid the temple, finding that it did not help them in their relationship with God. They continued to pray, recognizing their need for God, but Zechariah increasingly found that, when he was inside sacrificing or offering incense, they found it more helpful to pray outside.

A Message to Zechariah?

The increasing fruitlessness of the temple institution seemed to be a message to Zechariah that all of his hard work was bearing no fruit. But there was another far more personal sign of his failure that bothered him. His wife, Elizabeth, could not have a child. They tried and they tried for years, but nothing ever resulted.

This lack of fruitfulness devastated Zechariah. It was not his own personal disappointment that bothered him, or even that he felt heartbroken for Elizabeth who longed for a child. It was the knowledge that, if he failed to produce a son, his own priestly line that that went all to way back to the time of Moses would be broken forever. That seemed to him to be a failure that was a judgement of him. It seemed near impossible to bear.

But so it went. As the years went by, he kept hoping for change. But nothing happened. Herod died eventually, but he had so thoroughly corrupted the temple by making it a political tool that the institution only festered.

And nothing changed for Elizabeth either. Month after month, no life stirred within her and they began to fear that very soon there would be no months left. It would cease to be after the manner of women for her.

Those were the things that Zechariah was feeling when his section’s turn of duty came up and he set off to Jerusalem to do his temple service one more time.

An Offering of Incense

The lot fell to Zechariah that day. He had been chosen – chosen by God it seemed – to go into the sanctuary and burn the incense upon the altar. It was a task that had always felt so meaningful to him.

He would take the mixture of stacte, onycha, and galbanum that had been blended with pure frankincense and then beaten to a fine powder, and he would pile it up on the altar of incense in a great mound. Once he had lit it on fire, it would send up a sweet and aromatic smoke that he found pleasing.

But more than the smell of it was the sight of the white smoke climbing heavenwards in a straight line. He liked to imagine it ascending directly to the throne of the God of Israel – a sign of God’s close attendance to the fears and concerns of the people.

It made Zechariah feel as if he was given the privilege to personally bring the concerns of all the people directly into the heart of God even though the people were not here – even though they prayed outside, stubbornly rejecting their corrupted religion.

An Extraordinary Experience

But on this occasion, something truly amazing happened. As he breathed in the smoke, he calmed and he felt a great sense of expectation settle over him. Something was about to happen.

When the figure appeared, soft and insubstantial at first, like a being made of the smoke itself, he did not know what to think. Suddenly every sense in his body was heightened and he felt as if he was transported to another plane of being. A great trembling came over him, but he wouldn’t exactly call it a sense of fear – at least it was not Iike any fear he had experienced before.

“I am Gabriel. I stand in the presence of God, and I have been sent to speak to you,” the being seemed to say. And Zechariah knew that his faithfulness had not been in vain.

A Promise and a Sign

The promise that Zechariah received that day was very personal. He would have the son that he had always dreamed of. The impossible would become possible; Elizabeth would conceive and would have a son.

But he knew that this promise, as welcome as it was, was not just for the two of them. It was a sign. Just as Elizabeth’s womb, which had resisted for so long, would burst forth in new life, he knew that this was a promise that his faithfulness in the midst of a corrupted temple institution would also not prove fruitless.

He had felt as if he was getting nowhere for so very long. Surely those who were only bent on using the faith of ancient Israel to serve themselves – to enrich themselves or to pursue power and political domination – would continue to win. The small group of righteous priests who believed in what they did, would be forgotten as obscure and misguided idiots.

But now, because of this promise, he knew that God had not forgotten him. God might have bided God’s time, but God would not tolerate such things forever. That was the promise that Zechariah would cling to – even if he had to cling to it in silence while he waited a little bit longer.

The State of Christianity

I will admit that I sometimes get discouraged by the state of Christianity these days. I am not talking about the declines in membership or attendance that have struck the great majority of churches in recent years. There is something else that troubles me more.

I despair when I see people using the Christian faith as a tool to advance their own personal or political goals. I see people employing Christian leaders and teachings to persuade people to vote in ways that are ultimately against their own interests. I see them using the Bible (or bizarre interpretations of the Bible) to persuade people that they must hate immigrants or minorities or other marginalized people when the Bible teaches so clearly and consistently that we must do the opposite.

Alongside that, I see Christian leaders enriching themselves to the extreme and living lavish lifestyles while their donors only suffer. I see others using the power that they have amassed in their organizations to abuse and harass their own followers in abhorrent ways.

It is enough to cause many to lose their faith altogether, which it has indeed done in many cases. How many today, like in the story we read, are “praying outside” of the institution. They are holding on, however tenuously, to their faith in God, but they have lost all respect for the institutions of Christian faith.

The Situation in Herod’s Time

What we don’t realize is that that is the situation that we encounter in the opening of the Gospel of Luke. That is why Luke’s first words after his prologue are, “In the days of King Herod of Judea.” These words are not to set the date of the birth of Jesus. Luke will carefully set that in the next chapter. These words are meant for us to understand what was the state of the temple in which Zechariah served.

Herod was, without a doubt, one of the worst offenders in the history of Israel when it came to using the religion of Judea for his own personal and political goals. Everybody knew it and the people had lost respect for the temple institution because of it.

Faithful Zechariah

And so, I like to think that Zechariah would understand many of my own frustrations – serving within an institution that had been used by some to such nefarious ends. I marvel at his ability to be “righteous before God, living blamelessly.”

How did he do that for so long without losing heart – without giving up? I don’t know. But the fact that he did inspires me. The fact that God noticed and launched a renewal of the faith through his son, John, gives me hope.

I don’t know how righteous I am before God. Sometimes I wonder. I would also not claim to live blamelessly. But here is what I will say because of Zechariah, I will not cease to do what I can to live in such a way as to challenge all those who would use my faith for their own selfish ends. Will you do that too? I believe that that is the best way to honour the memory of a man like Zechariah.

Thank you!

Everything will always be all right when we go shopping!

Hespeler, December 1, 2024 © Scott McAndless – First Sunday of Advent

Jeremiah 33:14-16, Psalm 25:1-10, 1 Thessalonians 3:9-13, Luke 21:25-36

On their 2003 album, Everything to Everyone, the Barenaked Ladies included a song that always starts playing in my head around this time of year. The lyrics go like this:

Well you know it’s going to be all right. I think it’s going to be alright

everything will always be all right when we go shopping…

It’s always lalalalalala... let the shopping spree begin

lalalalalalalalala... everybody wins

So shut up and never stop let’s shop until we drop…

I remember many times when our kids were young, we would all pile into the car and head to the mall to do some Christmas shopping. As we headed down the driveway, we would put that very song on blaring from the sound system. It seemed to be the perfect thing to get us into the right spirit.

Shopping will Save Us?

But that song is about more than just how fun it can be to go shopping. It claims much more than that. It almost seems to be saying that shopping is what will save us – that it will be the thing that makes everything alright.

I am certain that they wrote it, not as a fun little nonsense song, but as a biting commentary on our society and its priorities. The song was written, after all, very shortly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. In the aftermath of those terrible events, the need to keep shopping became a dominant theme.

A week after the attack, the American president famously said to the American people, “I’ve been told that some fear to leave; some don’t want to go shopping for their families… That should not and that will not stand in America.”

The intent of that statement was certainly more nuanced than people usually give it credit for; I have taken it out of the original context. But the message that stuck, that many people heard was absolutely that if Americans stopped shopping, the terrorists would win.

Black Friday

As Black Friday, the biggest shopping day of the year and the kickoff to the Christmas shopping season approached in 2001, everybody was watching nervously. The very fate of the nation seemed to hang in the balance. If consumers came through, if they did indeed shop until they dropped, the nation would be saved. The salvation of society itself was in the hands of shoppers and dependent on their willingness to go even deeper into debt to keep the economy moving. Note how it was not up to the corporations or the retailers or even the financial institutions. We would only know that everything would be all right when we went shopping.

But it was not just true that year. This year, with people hit hard by inflation, a string of disasters and political uncertainty, you can bet that people are nervously watching the numbers on consumer spending during this season. It is so important that the federal government has even cut back retail taxes and promised a big stimulus check to keep people shopping. If the shoppers don’t come through, if they close their wallets and restrict their spending, it will be taken as a sign that we are all doomed. If, on the other hand, everybody goes shopping, well, you know that it’s going to be all right.

Retail Therapy

But there is also another meaning behind that song. Not only is it a reminder of just how dependent our entire system is on consumer spending, it is also a commentary on individual strategies for coping. For many people today, the motto that they live by is this: “When the going gets tough, the tough go shopping.” It is so common for people to distract themselves from their personal or global anxieties and fears by going out and buying something new that that people literally call it “retail therapy.”

When we buy something or when something we have ordered online arrives, we get that hit of dopamine that makes us feel, if only for a fleeting moment, as if everything really is all right. The feeling sometimes even lasts until the credit card bill comes in.

That is the world that we all live in. And the sense that shopping is what makes the world all right is particularly strong at this time of year. If you, as we are all expected to do after all, went shopping this weekend, you may have gone home with the feeling that, yes, everything is indeed all right.

A Different Message in Church

And then you come to church on the First Sunday in Advent, just days after Black Friday, and what do you get? Do you get reassured that everything is going to be all right? No, you do not. Let me tell you what you get on the First Sunday in Advent. You get “signs in the sun, the moon, and the stars.” You get “distress among nations confused by the roaring of the sea and the waves.” And you get people fainting from fear and foreboding of what is coming upon the world, for the powers of the heavens are shaken.

Those are words that were written almost two thousand years ago and were written in the shadow of some truly horrendous events – the invasion and destruction of an entire nation, the demolition of a temple and the wholesale slaughter of fighters and civilians alike. But they don’t really seem to be talking about ancient history, do they? They seem to be a pretty good commentary of the state of the world right now.

What’s Going on in the World

“Distress among nations confused by the roaring of the sea and the waves.” That sounds exactly like several reports on the effects of hurricanes that are still ringing in our ears from over the last couple of months. And I don’t know about you but my social media feeds are just chock full of “people [fainting] from fear and foreboding of what is coming upon the world.”

The ideas that are conveyed in this passage are painfully current – so much so that I suspect that many of us try not to think about the state of the world. In fact, that is one reason why we distract ourselves so very much with our “retail therapy.”

I can well imagine, therefore, that some people could be annoyed to come to church on the First Sunday in Advent and to open our Bibles only to be confronted with a gospel passage like this one which seems to be ripped from our newspaper headlines. Isn’t coming to church supposed to make us feel good? Aren’t we meant to be assured that everything is going to be all right? Because if the church won’t tell us that, we can always go to the mall!

Hope

And isn’t this First Sunday in Advent in particular supposed to be all about hope? I mean, we lit the candle and everything! All of this doesn’t seem particularly hopeful, does it? It seems downright disturbing.

Well, that takes us right to the heart of the question of the day. What is hope? Is hope just a good feeling, an assurance that everything will be all right? It is not. Yes, it is true that one aspect of hope is a confidence that things will work out in the end. But there is a difference between a confidence and a feeling.

Hope cannot be engendered by ignoring the real-world problems around us, which is what we often do with our shopping obsession. And I’m not just talking about how we distract ourselves by buying stuff.

People Struggling

I’m also talking about how lots of people are struggling because they are falling through the cracks of our economy. They can’t get work that gives them enough hours or enough pay to cover their bills. They can’t get housing that they can afford. They don’t have enough to buy healthy food. That is where an increasing portion of our population finds itself.

If the economy made any sense, such a situation would lead to utter collapse in every sector, but that is not what happens because we all go into debt to keep shopping. This hides the reality of the world we’re living in and it means that we don’t have to deal with it.

But hope doesn’t hide from the truth. It believes in the future, but not because it knows that the system is stable. It recognizes that the system is corrupt and teetering on the edge of collapse, but it still has confidence in a future. That is the hope that we celebrate on the First Sunday of Advent.

Eyes Wide Open

The passage we read this morning from the Gospel of Luke is based on the words of Jesus. He spoke them to his disciples as he looked forward to the chaos and destruction that he knew would be visited on the people of Judea if they continued down the path that they were on. But Luke wrote these words decades later, when many of the things that Jesus had foreseen had already happened and the world was still a mess.

Both Jesus and the gospel writer looked at the world with eyes wide open. They saw the mess. They saw the injustice and the failures of the systems. And yet they still had hope.

They had hope, not because they knew what the outcome would be so much as because they knew in whose hands the future would be. They had hope that allowed them to look realistically at the situation in front of them, to come to terms with just how scary or anxiety inducing it was, and yet accept that it was the reality they had to deal with. They could embrace it because they knew that God was alive and that God would never abandon God’s people.

Not Very Good at Hope

I don’t think that we are very good at hope in our world today. We are more in the business of spreading good feelings or of distracting people with things like consumer spending. It is why so many of us have such a hard time once the distractions stop. We are all constantly scrolling from one tik-tok or tweet to the next on our phones, we always have the television or the music on in the background because we know that, if ever the distractions stop, the bleak reality of the world will come crashing in on us and we won’t be able to cope.

What Else We’re Distracted from

But Christians should know that there is another possible thing that happens when we turn off the distractions. People of faith have discovered again and again down through the centuries that when you enter into true silence – when you turn off the distractions and the voices within you – something amazing can happen. You can encounter God.

That’s another reason why the distractions – including the shopping obsessions – of our modern world get in the way of hope. They may be keeping us from being disturbed by the evil of this world, but they are also preventing us from finding God, the source of all hope.

Powerful Image

This is the image that Jesus places before us to find hope when things are looking dark: “Then they will see ‘the Son of Man coming in a cloud’ with power and great glory.” I don’t personally think of that as something that will happen once in practical terms. I see it as a promise of what will happen whenever we seek for God’s presence. We will see the Son of Man coming in a cloud with power and great glory.

This vision of the glory of God’s own mighty Son is what can keep us going even when all seems lost.

That is why “when these things begin to take place,” you don’t need to fall into despair and you don’t need to distract yourselves with shopping. You can “stand up and raise your heads,” because you know that it is not shopping that will make everything be all right. You will know that “your redemption is drawing near.”