#FREEDOM!

Hespeler, 29 May 2022 © Scott McAndless

Acts 16:16-34, Psalm 97, Revelation 22:12-14, 16-17, 20-21, John 17:20-26

If there is one word that, above all others, people are disagreeing over and fighting over in our days, that word has got to be freedom. We are just hearing a whole lot about freedom. It was the cry on the lips of the people who forced their way into the United States capital on January 6th over a year ago. It was the resounding cry of trucker convoy protesters who occupied the heart of Ottawa earlier this year. It continues to be heard all over the place in protests against pandemic mandates that are mostly no longer in place.

And how many candidates in the ongoing Ontario election have been dogged by protesters shouting about this very thing? Meanwhile, the people of Ukraine are fighting for their freedom while the Russian president proclaims that he ordered the invasion of Ukraine in order to bring those people freedom.

No one is Anti-Freedom

The word has never had more currency, it seems. But, of course, while we are doing all this fighting over freedom, there is nobody who will stand up and claim to be on the opposing side. No one is going to claim the title of being anti-freedom and indeed almost everyone claims to be fighting for it. So, it actually turns out that what we are fighting over is not freedom itself but actually the definition of freedom. That was why I was so interested when I first looked at our reading this morning from the Book of Acts. The word freedom doesn’t actually appear in the story – not even once – and yet this story is all about the meaning and practice of liberty.

An Enslaved Woman

The story opens with a woman who is the absolute opposite of free. She is identified as a female slave which means she has no freedom in this world. She is also possessed by a “spirit of divination,” which was understood to mean that she would lose control of her mind in ways that forced her to foretell the future.

Of course, we might be inclined to diagnose her, if we encountered her today, as having some sort of mental health issue while they spoke of her condition in purely spiritual terms but, however you understand it, she pretty clearly does not have conscious control over what she says and does. That is a particularly devastating kind of slavery.

The Enslaved Men

The next people we meet in the story – the actual main characters – are also not free. It is the female slave herself who points this out when she cries out for anyone to hear, “These men are slaves of the Most High God, who proclaim to you a way of salvation.” And I don’t think that it is an accident that these two men are described using the very same term that is used for the female slave. They also need to be understood as being not free. But, pretty clearly, their slavery seems to be a little different from hers.

These two slaves of the Most High God, Paul and Silas, do have an objection to what this female slave says about them. Paul becomes annoyed with her. This is not because what she is saying is untrue, but simply because he doesn’t like all of the attention that that is putting on him. And so, he sets her free from this condition that has enslaved her mind and spirit.

The Only Free People

It is at this point that we meet the only literally free people in the story. They are the people who own the female slave. And I would draw your attention to the fact that it is these people, the only free people, who are the ones who complain about the loss of their freedom. They are upset with Paul because they believe that he has infringed upon their freedom of commerce. They made lots of money by means of the oracles of this female slave, and their complaint is that Paul has now deprived them of their freedom to profit.

Two Imprisoned Slaves

As a result of this, Paul and Silas, these slaves of the Most High God, are deprived of their freedom. They are thrown into prison and their legs are locked into the stocks. And then what happens? God intervenes in the story to set Paul and Silas free. So, do you see what I mean when I say that this story is all about the meaning of freedom. And, as I look at this story, I really do think that it could help us a lot as we try and sort out the really big arguments we are having about freedom these days.

Of course, the freedom that is at stake in most of this story is not really something that we have direct experience of. We are very fortunate, of course, that none of us has experienced firsthand the scourge of slavery, either as slaves or as owners. Perhaps more of us have some experience with mental health issues, either our own or those of the people we care about, but I know of few who have had to deal with issues that resulted in the loss of the freedom of their minds. And, of course, most of us are fortunate not to have had any experience of either just or unjust incarceration.

Think of the Poor Owners!

So, what is the closest point of contact to the question of freedom that we have in this story? Well, I would say that the kind of freedom we hear most talked about these days is the freedom of the owners that gets disrupted. So let’s just focus in on that for a few minutes.

Indeed, let us just try to have a little bit of sympathy for these poor owners. First of all, let us note, that “owners” is plural. This female slave doesn’t just belong to one master. And it is is not just some mom and pop operation that purchased her either. No, she belongs to a corporation. A bunch of people formed a corporation in order to buy up slaves who had special skills like this young woman. They invested their money with the expectation that they would be able to exploit their property without limit. They’ve got stockholders to think about. Can’t somebody think about the poor stockholders?

What of the Freedom to Exploit?

So, it is these corporate owners who scream loudest about their freedom and who manage to get powerful people to act on their behalf. It seems to me that this is something that still happens. When it comes to the freedom of corporations to exploit their workers, to manipulate their markets or to protect their profits, such freedom seems to be near absolute still today.

But it goes much further than that because, not only are the owners a corporation, they are also part of a privileged class in that society. And people who are particularly privileged for any reason, often simply cannot see how their exercise of privilege might impinge upon the freedom of others. These owners simply cannot see how much damage they are doing as they profit off of the exploitation of a young woman who is deep, deep in bondage.

The Freedom of Paul and Silas

So, that is one ideal of freedom that we see in this passage and, I don’t know about you, but I don’t find it particularly inspiring. But there is another idea of freedom in the story. Paul and Silas do not have freedom as the world defines it. They are the slaves of the Most High God and then they are thrown in prison and clapped in stocks.

And yet then, when they are at their most unfree, they do not act like it, do they? They start singing hymns of praise to their master even in their confinement. And then the story takes a strange twist when their master, the Most High God, intervenes to grant them their freedom. There is an earthquake, and they suddenly are freed from their bonds while the doors of their prison are flung wide open.

What they do with their Freedom

But here is the really fascinating part of the story. They react to this new freedom of theirs in almost the exact opposite way of the slave owners. You see, they realize something that the masters clearly do not. They recognize that their exercise of freedom will negatively affect the freedom and safety of others. You see, it was common practice for guards who permitted a prisoner to escape to be severely punished and even put to death for their failure.

Yes, the guard who was over that prison was just as unfree as Paul and Silas were in many ways. When he sees the aftermath of the earthquake and concludes, without even needing to bother and check, that the prisoners must have all escaped, the guard is ready to fall upon his own sword to escape such punishment and dishonour. But Paul, though he has been granted freedom by God, has actually not chosen to use that freedom in a way that will impact the life of the guard. He and Silas, and indeed all of the prisoners, have not escaped and so Paul shouts out to the guard, “Do not harm yourself, for we are all here.”

The Reaction to Such Freedom

Do you realize that what Paul and Silas do in the story is precisely the thing that gets people labeled as sheep (which is a short form for accusing people of not being free) these days? People go around loudly proclaiming that, because they are free, they do not have to do things for the sake of the safety and well-being of others. They mock and criticize people who make the choice to curtail their own freedoms for the sake of vulnerable people or for the larger community. That is indeed a version of freedom, but I find it to be a lot more like the freedom of the slave owners than the freedom experienced by Paul and Silas.

A Desire to Experience More Freedom

Paul and Silas have been set free by God, but they make a choice to express that freedom by prioritizing something else. They choose instead to value the salvation of the guard. And I mean by that that they literally save him from death at his own hands or the hands of his masters. But then the guard, having been given a taste of true salvation is not satisfied. He needs more. “Sirs, what must I do to be saved?” he cries out.

He immediately assumes that these people, who have chosen to value his salvation above their own freedom, can also save him in ways that go deeper and further. He is, of course, correct in this assumption. They answer him, “Believe on the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved, you and your household.” They tell him that he will find, in this Jesus, salvation so powerful that it extends even to his entire household.

Lessons on Freedom

So, then, what does this story teach us about freedom in this moment when it is such a volatile concept? It certainly shows us that freedom is an incredibly valuable thing. We certainly ought to prize the freedoms that we have. We should not let them be eroded away and should do our very best to make sure that more people should have such precious freedom.

But I also think that this story is telling us that freedom is not an end in itself. Freedom that is used to exploit the minds and the bodies of others in the pursuit of our own goals is not an inspiring form of freedom and is not one that we should aspire to.

Freedom we Choose not to Use

The freedom that is truly valuable is the freedom that we sometimes choose not to exercise because we care about others. And when we do that, when we choose to lay down our freedom because it may save somebody else, the promise seems to be that such salvation, so dearly bought, is so powerful that it may just spread far beyond our one little act of care and compassion for others. And that is how the good news and the message of hope will spread in this world.

When the Apostle Paul wrote to the church in Galatia, I cannot help but wonder if he was thinking of incidents like this one when he penned this: “For you were called to freedom, brothers and sisters, only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for self-indulgence, but through love become enslaved to one another. For the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself.’” (Galatians 5:13 -14)

Paul was clearly someone who understood a few things about freedom that still seem to elude us today. But I’m hoping that maybe we might be able to learn something from him.

Faith @ Home

Small Man, Big Amends

Faith @ Home

The Scandal of God’s Grace

Hespeler, 15 May, 2022 © Scott McAndless

Acts 11:1-18, Psalm 148, Revelation 21:1-6, John 13:31-35

In 1985 there was a movie that swept the awards of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. It won eight Oscars including best picture, best director, best actor and best writer. So, I am pretty sure that you have heard of this movie. And I wanted to remind you of it today because I think that it contains a perfect illustration of the scandal behind our reading this morning from the Book of Acts.

Beloved of God

In fact, the film zeroes in on the central dispute of our reading so perfectly that it is right there in the title. The movie was called, in case you haven’t guessed yet, Amadeus. Amadeus is a Latin word that means beloved of God. And the scandalous nature of the love of God is at the centre of the story. The titular character is, of course, none other than the great composer, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, but the main character in the story is the Italian composer, Antonio Salieri. The plot centres around a kind of obsession.

Salieri is jealous of Mozart because of his musical genius. But it’s about more than jealousy. Salieri is angry at Mozart for being so talented, but he is actually even more angry at God. At one point he declares this, speaking directly to Jesus in the form of a crucifix on the wall: “From now on, we are enemies – you and I. Because you choose for your instrument a boastful, lustful, smutty, infantile boy and give me for reward only the ability to recognize the incarnation. Because you are unjust, unfair, unkind, I will block you, I swear it. I will hinder (and remember that word, hinder) I will hinder and harm your creature as far as I am able. I will ruin your incarnation.”

Salieri’s Complaint

He recognizes, and I believe he recognizes correctly, that there is divine inspiration behind what Mozart is able to produce. It is a gift of God. But he is scandalized that God should give such a gift to a person like Mozart. He doesn’t work hard to produce it because he doesn’t need to. But, even worse, he does not live a virtuous life as Salieri defines virtue. He is licentious, vulgar and silly. Meanwhile, Salieri has worked and works so hard and lives a life of extreme piety and virtue, and yet the only music that he can produce reeks of mediocrity.

Salieri finds the very idea that God could give such good things to a person so unworthy so objectionable that it drives him to do awful things. It drives him to theft, corruption, attempted murder and ultimately to madness. Now, I think I ought to say in defense of Salieri that the film, though based on historical characters, is mostly fictional. The two composers seem to have actually had a pretty good relationship. But at the same time, there is something that is fundamentally true about the story of the film. There really is something very objectionable about the love of God and the gifts that it gives, something that we need to come to terms with.

Peter Visits the Wrong People

In our reading this morning, the Apostle Peter gets into a lot of trouble with the leaders of the church over this very issue. He has just come back from a visit to the home of a man named Cornelius where he ate and drank with the household, preached the gospel to them and shared with them the gift of the power and presence of the Holy Spirit. When he returns, however, the people in the Church of Jerusalem are very upset with him. The thing that bothers them is not that he has been preaching the gospel or sharing the love of God or even the gift of the Spirit. This is exactly what the church has been doing ever since the beginning and Peter has done no differently.

No, the only thing that is wrong about what Peter has done is who he did it for. He did it for people who everyone in the Jerusalem church agrees are just the wrong kind of people. They eat the wrong kind of food. They don’t follow the right laws. They’re not even circumcised! They just don’t deserve hearing the good news and they certainly do not belong in the community of the church.

A Personal Question

And I know that we often think of this as a one-time, very special controversy in the life of the early church. It was this important question about whether Gentiles and people who did not follow the Jewish law could have a place in the church. But, as this particular story makes very clear, at the level where this actually touched and affected people’s lives, this was not a theological question. This was a very personal question. It was all about God’s love and grace being lavished on a group of people who simply did not deserve it because of who they were and how they lived their lives. The Jewish Christians in Jerusalem were upset with God for the very same reason that Salieri was upset concerning Mozart. God was just loving the wrong sort of people.

And, given that this is a controversy that arises again and again throughout the history of the church, I think it is worth taking a good look at how Simon Peter responds to the objections of the church in Jerusalem. He responds to them by telling the story. He tells the story that illustrates that God, despite their limited understanding of what God can do, has clearly decided to love these people anyways by giving to them one of God’s greatest gifts, the gift of the Spirit. And then he ends his story with a statement that I believe should be engraved upon the heart of every believer, should be posted as a sign upon every one of our churches. He says, “If then God gave them the same gift that he gave us when we believed in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could hinder God?”

Who is Peter?

Think of that. Here we have the man who is generally thought to be the first great leader of the church, the one that Jesus called The Rock and perhaps the man who knew Jesus best, and yet he is saying, “who am I to hinder God?” And, given the context, what he is especially saying is, “Who am I to hinder God giving God’s love, gifts or grace to anyone?” And yet I see all the time people who seem to believe that they are exactly the kind of people who can hinder God in that way. That’s why I think that we need to learn, with Peter, to ask ourselves that question: who am I to hinder?

How we Hinder

I do believe that that kind of hindering happens all the time in the church. You know, every time we look at somebody who comes into contact with the church and we decide that they don’t really belong and so don’t make them feel particularly welcome, we are hindering God doing God’s work in their life. If you decide that somebody isn’t dressed well enough and communicate that to them even in a subtle way, are you not hindering them from being recipients of the grace and gifts that God is giving through the church? And it’s the same if you decide that based on race, on class or wealth or age or orientation or gender identity or whatever other criterion you can come up with.

I’m not saying that we do it intentionally, because sometimes we’re often not aware of the subtle ways in which we make people feel like they do not belong. Sometimes it’s just a matter of not taking their ideas or opinions seriously. Sometimes it’s not even considering including them in our little circle of friends. But, make no mistake, we all do it sometimes. And we need to ask, who am I to hinder what God wants to do in their life through the church?

Other Ways of Excluding

But do not only think of this in terms of the kind of grace that usually comes to mind in the life of the church. This is something that we do in many other circumstances as well. How often do we write somebody off – do not consider them for a job, or we write off their thoughts and ideas or any potential contribution they could make – for reasons that simply do not matter? You just never know what God might have in mind to do for that person or through that person and yet because of some prejudgment on your part you can hinder that from happening.

Who Can be Saved?

This also applies to our talk and thought about salvation. Christians have a long history of having a very narrow understanding of who is worthy of being saved by God. We confess, of course, that salvation is by grace through faith, but we often have a very narrow understanding of what that faith has to look like.

In particular, we expect it to look like the faith that we have professed. So, if someone believes differently or puts more emphasis on how they live out their faith than on believing all the same things that we believe, we might easily come to the conclusion that they are not worthy of being saved. I don’t think we realize how, when we do that, what we are really doing is putting limits on the love of God. We are deciding that we are the ones who can hinder what God wants to do in people’s lives.

Who Does it Hurt?

When, in the movie at least, Salieri decides to hinder God’s decision to be gracious to someone that he did not think deserved it, he did not hurt God. The message of the movie, in the end, is that he really only hurt himself – ultimately driving himself to madness. And that is the true tragedy that comes when we seek to hinder the grace of God from being shown in somebody else’s life. We will not stop God from being gracious. Thank heavens that we do not have that power. We will only hurt ourselves. For know this above all, God loves those who love amadeus, who loves those who, however unworthy in our eyes, are beloved of God. And, what's more, I honestly believe that the more we embrace this truth, the more that we will understand for ourselves how truly beloved we are to God.

Faith @ Home

Why pray?

Hespeler, 8 May 2022 © Scott McAndless

Acts 9:36-43, Psalm 23, Revelation 7:9-17, John 10:22-30

Our Bible story from the Book of Acts this morning is really a very uplifting story, isn’t it? We have this woman, Dorcas, and she is a simply wonderful woman. Everybody loves her. She makes all of her friends these beautiful clothes that they treasure. And yes, she gets sick and dies and that is so very sad. But then Simon Peter shows up, he prays and he raises her from the dead and basically everyone lives happily ever after. It is just so beautiful. It reminds us of the power of the resurrection of Jesus to renew our own lives and to give us the hope for a life beyond this one.

A Few Questions

So, it is absolutely a feel-good story. And yet, at the same time, it is also the kind of story that, when you look at it closely, is going to make you ask a few questions. We’ve talked about prayer, and it certainly makes you ask a few questions about prayer.

Questions like, what if Simon Peter hadn’t been in a nearby town so they could ask him to come and pray for her? Would God have just left her dead simply because there wasn’t a good enough prayer around? And what about all of the other really nice women who made beautiful clothes that didn’t have Peter to pray for them? Why wouldn’t God care enough to raise those women?

And then there is an even more delicate question about prayer in general. Why is it necessary? I mean, apparently God had already decided that he was going to raise Dorcas. The story ends by telling us, “This became known throughout Joppa, and many believed in the Lord.”

Why Would Prayer Change Anything?

That seems to be the point of it. God wants the message to spread and raising somebody from the dead is definitely a public relations coup! So, if God had already decided to do it, why did he need Peter to ask? And if God didn’t want to do it, why should the almighty Creator of the universe be persuaded to change plans just because this one guy asked God to do it?

In short, the question is, why pray for these things? If God already knows what we want, then why do we need to ask? If God is really in charge, why should we think that God might change course on something just because we ask? These are all really good questions, and they deserve answers.

Transactional Prayer

The root problem, I think, is this. We just don’t understand prayer the way that God does. We tend to think of it, like we do most things, as a transaction. You go into the candy store, you slam down your toonie down on the counter and the cashier gives you a box of Reece’s Pieces®. That’s a transaction. And we think of prayer that way – we do an act of devotion for God, or we ask in just the right way in just the right words, and God gives us the thing that we want in return.

Based on a Certain View of God

The biggest problem with that way of thinking about prayer is the picture of God it is based on. It presumes that God is somewhere “out there,” and that prayer is the post office or the email server that we can use to contact God in that distant place. But here is the thing, God is not “out there.” God is certainly not just up there in the sky looking down. If God is truly God, then God is right here. God is right beside you, perhaps closer than anyone has ever been. Come to think of it, if God is God, then God must be in some sense already within you.

So, of course, when you think to pray and ask for something, God already knows that you need it. God is a part of that need. When you worry and pray for someone who is sick or in danger, God already feels your sorrow, anxiety and fear for that person. Prayer is not a transaction, it is participation. It is God participating in what you need or in what you are feeling. It is you participating with God in the ongoing work of creation.

A Master Dancer Seeking a Partner

On one level, yes, I would affirm that God does not need us to pray in order for God to do whatever needs to be done. But, on another level, I would say that God acting without us entering into that conversation of prayer would be kind of like a master dancer who was able to do all of the steps absolutely perfectly and flawlessly. But the problem with that is that the best Tango dancer in the world cannot dance the Tango without a partner.

God wants you to be that partner. It’s not because you have to say the right thing or do it in the right way. It’s not even because you know all of the steps of the dance. God wants a partner. God wants to give you the privilege of being part of the dance.

Or think of prayer as a song. When you pray, you get to put your concerns into words, however imperfectly, so that God can take up your melody and sing the perfect harmony. That’s what prayer is, not a transaction. It’s a dance, it’s a song, it is an exercise in making that eternal connection between the human and divine perceptible, even if only for a moment. So, yes, let us pray!

Faith @ Home

Can People Really Change?

Hespeler, May 1, 2022 © Scott McAndless

Acts 9:1-20, Psalm 30, Revelation 5:11-14, John 21:1-19

I would like to begin by saying that I am very much on Ananias’ side in our reading from the Book of Acts this morning. Ananias receives a vision in which Jesus himself appears to him with some very specific instructions: “Get up and go to the street called Straight, and at the house of Judas look for a man of Tarsus named Saul. At this moment he is praying, and he has seen in a vision a man named Ananias come in and lay his hands on him so that he might regain his sight.”

It is a wonderful thing, of course, to be on the receiving end of such a vision, but Ananias hesitates. “But Ananias answered, ‘Lord, I have heard from many about this man, how much evil he has done to your saints in Jerusalem; and here he has authority from the chief priests to bind all who invoke your name.’” And I just want to pause here and affirm just how very wise Ananias is to hesitate here.

Hesitation is Good

Ananias is completely right (and the Lord does not contradict him) that Saul has been an extremely violent, abusive and angry individual. His mistreatment of the followers of Christ has been so egregious that the reports of it have spread far and wide. He is feared in Damascus because of things he has done almost 300 kilometers away. The point that Ananias is making is that abusive and violent people don’t just change and I feel that I need to underline the simple fact that he has a point. At the very least, we need to be very skeptical when they profess that they have.

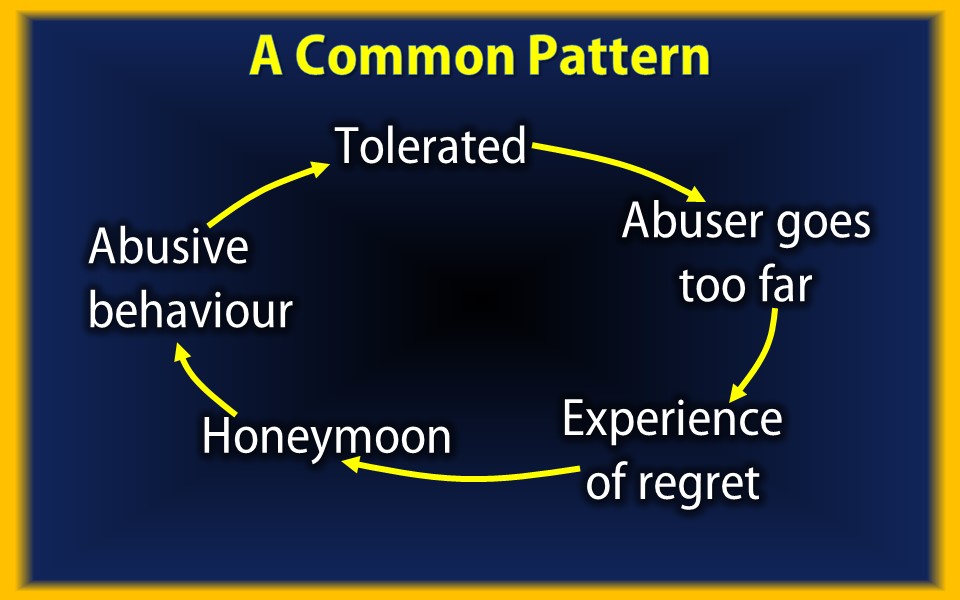

A Common Pattern

For example, anyone who has ever experienced domestic abuse (or has counselled people who have) would definitely be with Ananias at this point. There is a familiar pattern that emerges in many cases of domestic abuse. The abuser (often but certainly not always a man) has a tendency when frustrated, thwarted, intoxicated or otherwise affected to lash out with verbal or physical violence. The victim may tolerate a certain level of this abuse – not because they should, of course, but because it is just human to want to maintain an important and meaningful relationship.

But the abuser will eventually go too far – will do something that scandalizes even themselves or that threatens to expose them for who they are because of the visible damage that they have done. At this point, the abuser will often have an intensely powerful experience of repentance. They will express intense sorrow and regret. They will, above all, loudly proclaim that they have changed, that they have learned their lesson and they will never behave so abominably again. At this point the victim may well forgive them because, as I say, people often feel that they have to maintain the relationship at all costs.

A Honeymoon and the Disappointment

What then follows is a period of time that might be called a honeymoon. Oh, the abuser becomes extremely respectful and caring towards the victim. It is the best of times. But here is the problem, when that is the pattern, the honeymoon never lasts. Sooner or later, something triggers the abuser and the whole cycle begins all over again.

So, if you have ever experienced abuse or you love someone who has, you can certainly be forgiven for being dubious when abusers proclaim that this time is different, that this time they have changed. In fact, by the time most victims finally get to the place where they choose to save themselves and the other people they love by escaping, they have been through that cycle so many times that it’s quite understandable that they then have a very hard time trusting anybody who says that change is even possible.

Also in Race and Group Relations

And I would also note that this is something that we see, not only in personal relationships, but in relationships between groups. How many times have we seen incidents of racial violence against minority groups where the majority were so appalled that they made these incredible promises that everything was going to change, and how many times have those promises been broken?

This is something that seems particularly poignant in Canada in the wake of finding so many secret burial sites at residential schools. Do you remember the promises that were made in the wake of that scandal? Do you remember the pledges that have been made about nation-to-nation relations, on ratifying the terms of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, of getting potable water in Indigenous communities? How many times have we said that this time it is going to be different? Every time we do that then don’t really follow through, it just becomes harder for anyone to believe it.

And Yet Change is Possible

So, yes, Ananias raises a very important issue in the midst of his vision of the Lord Jesus. But, as much as I appreciate him raising it, I do not want to fall into complete cynicism. Yes, people who have been abused or endangered by others are understandably reluctant to believe that people can really change. And yet, it is important to say that it is not impossible. People do change.

Saul, who came to be known as the Apostle Paul, certainly did change. He changed radically. And if we are not going to give up belief in humanity altogether, we need to believe that he is not the only one in the history of the world to do so. So how do we know when change is really possible? And how can we tell when an abusive person is just starting the old cycle of abuse all over again? Maybe that is the question that Ananias is really asking.

A Focus on Intense Experience

When people try to convince us that they have really changed, what do they tell us? They usually try to persuade us by speaking about the intensity of their regret or sorrow. They talk about how deeply it affected them when they realized what they had done was wrong. Can’t you just see an abusive domestic partner beating their breast and proclaiming their depth of feelings? Or remember how deeply we all felt our regret about the discovered residential school remains? Why we flew our flags at half mast for months so badly did we feel it!

But are such powerful experiences and expressions of deep emotion truly a sign that great change is coming? Well, certainly the experience that Saul had on the road to Damascus was powerful and emotional. It was powerful enough to knock Saul off of his horse, affecting enough to strike him blind. But there is a strange thing that I noticed.

How the Lord Convinces Ananias

When, in the midst of his vision, Ananias asks for something that will convince him that Saul could have changed, the Lord does not refer to any of that. The Lord does not say, “Don’t worry, Ananias, of course Saul has changed completely because I totally blew him away with my special effects budget.” Nor does he say, “You’ve got to understand that Saul feels really, really sorry for everything he did in the past.” Those are the kinds of things that serial abusers appeal to in order to prove they’ve changed and, as I said, it doesn’t actually inspire that confidence that we think it does.

So, what assurance does Ananias actually receive? “But the Lord said to him, ‘Go, for he is an instrument whom I have chosen to bring my name before Gentiles and kings and before the people of Israel;I myself will show him how much he must suffer for the sake of my name.’” So what is it that God thinks should convince Ananias that Saul really has changed? Not his powerful experience, not how sorry he feels, only one thing – the fact that God has given Saul a job to do.

A Sense of Purpose

You see, when God truly wants to bring about change in somebody’s life, that is how God works. What God does is offer people a sense of purpose; God gives them a job to do. This is very clearly signaled in the Book of Acts, particularly in this key story of Saul. Now, if you read very carefully the story of Saul’s experience on the road to Damascus that we read this morning, you do not actually get a strong sense that Jesus is giving him some task to do. The emphasis in the exchange between Jesus and Saul is only on the matter of Saul persecuting Jesus because of the ways in which he has been persecuting the church.

There is little more than a rather vague sense that there is a task being given when Jesus says to the blinded Saul lying on the ground, “But get up and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do.” Jesus instead tells Ananias what he wants Saul to do, that he has been specially chosen to bring the gospel to the Gentiles.

The Three Conversion Stories

The interesting thing is that this is something that becomes increasingly clear to Saul as he goes forward. The story of his experience on the road to Damascus is actually told three times in the Book of Acts. And each time, there are significant differences between the stories. Since the entire book was written by the same person, this cannot be something that just happened by accident. The author seems to be trying to reflect Saul’s (or as he eventually comes to call him Paul’s) growing understanding of what had happened to him. At first, yes, it might have all been about the powerful experience. But, by the third time Paul tells the story, he apparently remembers that Jesus said a little bit more than just, “I am Jesus whom you are persecuting.”

The third time the story is told, Paul recalls that Jesus went on to say, “But get up and stand on your feet; for I have appeared to you for this purpose, to appoint you to serve and testify to the things in which you have seen me and to those in which I will appear to you. I will rescue you from your people and from the Gentiles—to whom I am sending you to open their eyes so that they may turn from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to God, so that they may receive forgiveness of sins and a place among those who are sanctified by faith in me.”

Saul’s Increasing Understanding of his Calling

This is told this way in order to indicate Paul’s growing understanding of what it was that truly changed his life. Yes, the light that he had seen had been so bright, I mean literally blindingly bright. Yes, the experience that he had had of the presence of the risen Jesus had been so very real and it had remained with him ever since. But, the more he thought about it over time, the more he realized that these were not the things that changed him. Maybe they had gotten his attention, but it was something else that had actually changed the course of his life. It was the simple fact that he realized that there was something he could do – something his Lord was calling him to do and that he alone could do – that drove the actual change of his life.

Understanding for People who have been Hurt

Can a person change? The answer to that question is yes. And yet, I completely understand those who have experienced abuse at the hands of others and how they can be skeptical when they hear claims that any abuser has changed. I would especially counsel anyone who has experienced abuse to be very cautious when their partner comes along claiming that they have changed because of some powerful experience, realization or feeling of sorrow.

You are not necessarily required to trust someone just because they say such things. Trust is a very difficult thing. It can take years to build up and then can be broken in just a moment. Once broken, the task of rebuilding it becomes even harder and will likely take longer.

How to pursue Genuine Change

And yet change is possible. If you are looking to bring about significant change in your life or in your relationship, I would suggest that you should look beyond powerful experiences or even powerful feelings of regret. Real change will come when you embrace a new sense of purpose in your life and when you come to understand how God is calling you to create new possibilities and new beginnings for the world.

When things have gone wrong in relationships, whether in personal relationships or in larger relationships like that between a nation like Canada and its indigenous peoples, it is far too easy for us to focus on what the other person needs to do, how they need to forgive or how they need to get over it and trust us again.

That is not where real change will be found. But when we can get past expressions of regret and sorrow and take on a single-minded purpose towards changing the situation for everyone, we will find that God is able to bring about change both in us and through us.