Sunday, May 3, worship details

Devotion for May 1

Devotion for April 30

Devotion for April 29

Devotion for April 28

Daily Devotion for April 27

Today’s worship details, April 26, 2020

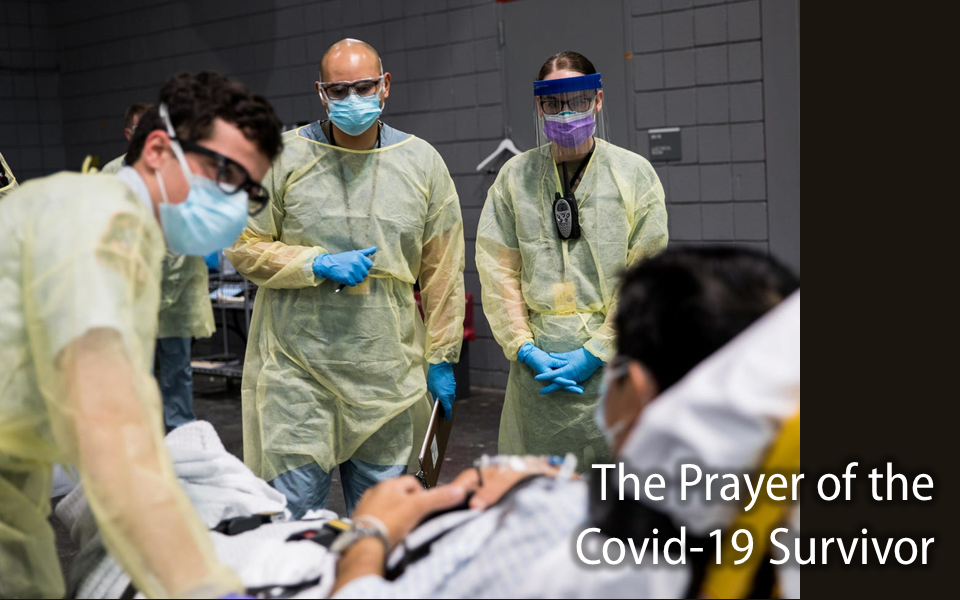

The Prayer of the Covid-19 Survivor

Here is a video of the sermon:

Hespeler, 26 April, 2020 © Scott McAndless

Acts 2:14a, 22-32, Psalm 116:1-4, 12-19, 1 Peter 1:17-23, Luke 24:13-35

There have been many stories over the last several weeks of people who were struggling to stay alive. They were in hospital, dealing with high fevers and shortness of breath. Some were taken into intensive care and even put on respirators. Others, for various reasons, were not taken to the hospitals but struggled all the same in their home or residence. That struggle was also often made much worse by a strong sense of isolation as people could not have their loved ones with them and those who did care for them could only do so behind several layers of protection.

This struggle with death is very real and all too many have not survived it. And yet we can also celebrate the fact that the great majority who have contracted this disease have not succumbed to it and that those who have suffered even from its worst symptoms have, in the majority, survived and come out the other end. We do remember and mourn those that have been lost and that might yet be lost. But today, I want us to also spare a thought for the survivors of this pandemic, and most of us will probably be able to put ourselves in the category of survivor. What does it mean to survive such a thing is this?

The psalm that we read this morning, Psalm 116, may be uniquely able to help us answer that question. There are different kinds of psalms in the Bible, written to be used in different situations by different kinds of worshippers. Psalm 116, does seem a little bit unique. It seems to have been written for people who are dealing with a very specific situation, but a situation that arises often enough. It is pretty clearly the prayer of someone who has been seriously ill and in fear of death and yet has survived. Presumably, this was the prayer that worshipers would pray once they had recovered, probably as they came to the temple and gave an offering of thanksgiving. That much seems clear when the worshiper prays, “The snares of death encompassed me; the pangs of Sheol laid hold on me; I suffered distress and anguish. Then I called on the name of the Lord: ‘O Lord, I pray, save my life!’”

Being thankful is indeed something that we all need to think about how we can practice as we look at our lives as survivors going forward. I think it will be helpful to all of us to be able to practice gratitude in small and large ways in months to come because those months will not be easy. But this psalm is not just about being thankful. Its main focus, instead, is on the life of the survivor going forward and what is going to be different.

Being a survivor, brushing close to death and yet surviving, has always had great power to transform people’s lives. This is something that the ancients understood, and it is absolutely reflected in this ancient psalm. One thing that people have a tendency to do when they are in brushes with death is to make vows and promises which is something we see in this psalm as well.

This may not be an entirely helpful impulse. One thing that people do, you see, when they are in fear of death is that they have a tendency to want to make bargains. People are afraid, of course. Fear in the face of death, even for people of faith, is a natural human response. And one human way of dealing with that fear is to try to make bargains with God or with the universe or with other key figures in your life – basically with whoever you feel might have the power to save you. This kind of bargaining is actually a way of trying to pretend that you have control over something that is ultimately uncontrollable. It is not really a healthy response, but we all have a tendency to do it anyways because we are scared.

So people will make promises to God – you know, donations, vows of chastity, promises to be a missionary, that kind of thing. It becomes an exchange; if God gives you your life, you will give this valuable thing in exchange. It is not really a good response because, first of all, God doesn’t work like that. God doesn’t make bargains for human life. As the psalmist says, “Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his faithful ones.” Nothing you could offer to God has more value to God than your own life.

God doesn’t make transactions with us over our life and death, but God recognizes that facing times like that – times when you don’t know if you’re going to make it – gives you a certain perspective on your life and priorities. I think we’ve all seen something of that in recent weeks. Do you remember all of those things that we got upset over or argued about with each other or with the people we loved just a few weeks ago, they were things that seemed so very important. But this pandemic has given us all a certain perspective – those things just don’t seem to matter all that much anymore. Lots of things don’t seem to matter as much as they once did – including perfect haircuts, deodorant and pants!

So living through this kind of crisis can and should make you think very differently about many things. And when you get a good look at your priorities in that situation, it is good to respond to that by seeking some change. I like to think that that is the kind of vow that the writer is talking about keeping with God in this psalm. So I think it would be good for us to think about the kinds of vows we really ought to make coming out of this thing.

Do you think that you could promise, for example, to hold on to some of that perspective once this disaster is all over? Could you vow not to fight with other people and not to make enemies of other people over matters that really are not of ultimate importance. Could you remember what is so clear right now, that people are more important than money, than whether or not your sports team wins and than maintaining certain practices of the status quo. I honestly feel as if many things could change if we, as individuals, could make such vows.

But there is something else that we have learned through this. If we’re going to make it through this thing – and we will make it through this thing – we will not just do that as individuals. We have to do that as a society together. I realize that that’s probably been about the hardest thing to pull off in this crisis, but we’ve also realized just how essential it is. So the question of who survives and what we learn by surviving is also a question we need to ask of society as a whole.

Our society has already done a certain amount of bargaining in this crisis. We have made the bargain that if we took some costly steps, like instituting social distancing and shuttering non-essential businesses, we would make it through and survive together. That bargain, prayerfully, will succeed. But the bigger question will be what will we learn as a society by surviving this thing? And what sort of vows moving forward do we need to make to enshrine those lessons into our recovered society.

The first lesson, clearly, is simply that, that we have to look beyond our welfare as individuals. You need to remember, moving forward, that your health is not only dependent on you. I may be healthy at the moment, but if my neighbour is not healthy or the homeless person down the street or the prisoner or the person on disability support or welfare is not healthy, then my health will be compromised.

This should absolutely prompt us all to give up on the myth that whatever success you are able to amass for yourself in this life is totally up to you. This should make us vow to look beyond the glory of individual success and discover how we can create a successful society together. Can we say, together with the psalmist, “I will pay my vows to the Lord in the presence of all his people, in the courts of the house of the Lord, in your midst, O Jerusalem.”

We have also learned through this pandemic that about $2,000 a month is apparently what an ordinary person needs to live within our society. But we have also learned that some of the people in our society, people that we have deemed essential for our survival, are routinely not paid that much. I’m talking about people like grocery store employees, warehouse workers, food delivery people, farm workers and a whole host of others who ensure that we can get the things that we need. Many of these people are paid minimum wage or less and that works out to be less than $2,000 a month.

Now, as far as I am concerned, if we do not come out of this crisis without learning something about that disconnection between somebody being deemed essential and their work being adequately compensated, we will have absolutely failed as a society. Can we say, together with the psalmist, “I will pay my vows to the Lord in the presence of all his people, in the courts of the house of the Lord, in your midst, O Jerusalem.”

What other lessons may God have for us in this pandemic? What about lessons for the church? There will be many. The church has done what many of us thought to be impossible during this time. We have learned to be the church without a building. The building is closed and locked. We cannot gather in it, nor can we use it as the base of operations. Almost everything we did before this all started was centered around that building – about attracting as many people into it as possible, using the building’s resources to feed and clothe and otherwise minister to people in the community, to fellowship together and support one another and above all to meet with God in a sacred space.

We have had none of that, and yet we have managed to continue to be the church during this time. Yes, it has not been as we would like it. And it may not always meet our needs or the needs of others in the same ways, but we have proven it is not impossible. So I think that we need to make a vow that, when the day comes and we are able to gather again in our building, we don’t just do what will feel most comfortable – we don’t just go back to being the church as we were. We need to think a whole lot more about how we are the church without the building, it will make us stronger in the building too. “I will pay my vows to the Lord in the presence of all his people, in the courts of the house of the Lord, in your midst, O Jerusalem.”

No one wants to go through a serious illness or crisis, but serious illnesses and crises are part of life in this world. We could get into some serious philosophical or theological discussions about why these things happen or why God allows them to happen, but the bottom line is we don’t actually have answers to those questions. What we do have is a God who cares about us and about what we struggle through and who is committed to walking through the worst with us. One of the big benefits of that is that there are things that we can take out of the story of our survival and that will lead us into better things going forward. So, by the grace of God, let us pay our vows to the Lord.