Hespeler, 22 July, 2018 © Scott McAndless

Genesis 17:1-8, Acts 2:37-42, Psalm 100:1-5

| I |

was raised in a Presbyterian Church as a part of a fairly typical Presbyterian family at that time which meant that I was baptized as an infant when I was only a few months old. Since I was born near the end of the famous Baby Boom and at a time when the vast majority of the children born in Canada were baptized, my parents stood at the front of the church with a large group of parents and we were all baptized one after the other in a kind of an assembly line.

And that wa s fine. I mean, I didn’t remember it, of course, but my parents told me that it had been done and I had no reason to be concerned that it hadn’t. But then I grew up and, in time, I came into contact with another group of Christians who didn’t do baptism in quite the way that it was practiced in my church. These Christians are collectively called Anabaptists – a group that includes denominations such as the Baptists and various kinds of Mennonites. These churches do not generally see a baptism that is performed on an infant as a valid baptism and will argue that, to be truly valid, baptismal candidates should be of an age where they can actually choose for themselves whether or not they want to be baptized.

And when I first came to know Christians who believed this way about baptism, I will admit that I found their position to be very interesting and even persuasive. It kind of made sense to me, this idea that baptism should be something that you enter into willingly of your own accord. In fact, I will even admit that I started to wonder whether maybe there was something invalid or even illegitimate about my own baptism.

So, yes, I went through a period of time when I questioned my baptism. And you know how it is when you are going through adolescence. Who doesn’t remember those days? You struggle with everything. If you are a person of faith, you almost inevitably question that faith at some point. You certainly struggle over your own moral choices and decisions and can be very hard on yourself when you (also inevitably) fall short. So I went through all of that too but, in some ways, it was complicated by the whole baptism question. I couldn’t help but wonder if my baptism was at the root of all my problems. Maybe if I had been baptized later, as a believer professing my own faith, it would have taken, it would have sunk in deeper and would have had a more lasting effect on my moral behaviour and my doubts. I suffered (and I am going to go ahead and hashtag this one because I think that it’s time) I suffered from #AnabaptismEnvy.

I suspect that I am not the only one. So I do think that the question that is raised in this morning’s reading from the Catechism is a very important one: “Who may be baptized?” Finding the answer to that question did not only put my own mind at ease regarding my own baptism, it also helped me to understand the real meaning and purpose of the sacrament.

First, let me clearly affirm what I learned as I matured as a Christian. Any struggles I had as I grew up and matured in my faith all stemmed from my own basic humanity and absolutely not from any deficiency in my baptism. I have known, and continue to call my friends, many Anabaptists. They are very fine people and highly committed to their faith and to doing what they see as right in the world. But the fact that they were baptized at a time and a place of their own choosing did not mean that they had been spared the struggles and the doubts that are common to all of us.

I have observed one thing in a number of cases: when a person comes to that point in their life when they decide to make their public commitment to Christ by being baptized, they will often go through a kind of a honeymoon period shortly afterwards. There will be a time when all is beautiful and wonderful and clear for them and their Christian lives are so easy. Such a time is a great thing and a wonderful gift for a person to experience. But the reality is that a baptism does not solve all your problems and unless you actually address the negative patterns and triggers in your life, sooner or later that honeymoon period will end and you will find yourself returning to old ways and old problems.

So, no, a baptism is not going to fix you. That is actually not what it is for. But what is it for? That is the question that really matters here, isn’t it? And to answer that question we really have to dig into the scriptures a bit. In our reading this morning from the Book of Acts, we find the Christian church at a very pivotal moment. It is several weeks after the resurrection of Jesus and the church is having its big coming out moment on the Day of Pentecost. Up until then there had been a discipleship group around Jesus – a group that is said, at one point, to have included at least 72 people. In other words, it wasn’t exactly huge. It was a somewhat limited group and its focus was not really on growth in numbers. But all of that changes as the church makes its big debut on Pentecost.

So after a bit of a fire and light show in which flames descend upon the heads of individual believers followed by a pretty impressive display of the disciples’ ability to speak a huge number of strange languages, the big moment arrives. Simon Peter gets up and preaches the first sermon of the Christian Church – a sermon that he begins, by the way, by saying, “Ladies and gentlemen, I know that we might look like it, but these people are actually not drunk.” That is personally my favourite first line of a sermon in all of Christian history.

But, however it begins, it is obviously a very persuasive first sermon because, at the end of it, a huge number of people – Luke says that there were three thousand of them – want to become a part of whatever this new thing is. “Brothers,” they say, “what should we do?”

This is an incredibly important moment. A movement is defined by its membership and so there is a real need to know who belongs. If you are organizing a new club, for example, you might set up bylaws or standards of dress or behavior. Only those who agree to abide by these things can belong. When you are starting is also the best time, of course, to establish membership fees. This is because, above all else, a movement is defined by who is in and who is out. So what Peter says next here is going to define the church for the next two millennia.

And what does Peter say? Are there any rules of behavior? Are there any dress codes, any fees? No. This is what Peter says, “Repent, and be baptized.” That is it. If you read the entire sermon, it is clear what Peter means when he says, “repent.” He has just spent several minutes describing the corrupt system of this world – the system that put Jesus to death. Based on everything that he has just said, to repent clearly means to give up and turn your back on the corrupt system of this world and seek a new basis for life. That is the only requirement and it is basically an exasperation with this world and its delinquent ways. It is about a desire to see change and to be a part of that change.

And, it is with that understanding that Peter offers the next step which is baptism: “be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may be forgiven; and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.” What then is baptism? It is an outward sign that you belong to a different system.

The most important explanation of the meaning of baptism in the scriptures sees it as an image of dying and being raised up to new life. “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death?” Paul writes to the church in Rome. “Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life.” Dying to something old in order to be raised up to something new is about the clearest image you could find of turning your back on one system in order to embrace another. That is exactly the same kind of transition that Peter is talking about in the Book of Acts.

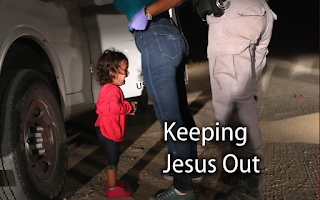

So, more than anything else, baptism is a declaration of what system you belong to, of where your allegiances now lie. It is not a statement that you understand everything, that you have all of your beliefs worked out or that you have all of the answers. This Peter makes quite clear when he continues to speak to the Pentecost crowd, “For the promise is for you, for your children, and for all who are far away, everyone whom the Lord our God calls to him.”

To the all important question of who may access this incredible power of baptism, Peter gives the clear answer, there are no real limits. It is for you, yes, but also for your children and note that no age limits are given. Even more surprisingly, he says, it is for those who are near – those who are already sympathetic to the message – but also for all who are far away and may have no understanding of these things. And he leaves the reason for this until the last when he declares that ultimately the grace that is received in baptism does not depend on the person who is being baptized themselves but only on the calling of the Lord our God.

So how is this any kind of answer to the question of Anabaptism envy? The Anabaptists are indeed correct that it is good to come to God and, as a competent adult, choose for yourself to be baptized as an act of personal commitment. And, of course, many people do exactly that in many different churches including our own. But Peter makes it clear in this passage from the Acts that this is not the only way, nor is it necessarily a superior way. This is because the grace of the baptism is not dependent on us but on God. And God can and does make a place for everyone. Can the person who has such a reduced mental capacity that he will never understand the meaning of baptism be baptized? By the grace of God yes. Can an infant who may or may not someday choose for herself to be a follower of Christ be baptized? By the grace of God, yes.

For baptism is nothing and has no power if it is not a celebration of the grace of God and no one can put limits on the limitless grace of God. The promise of baptism is a new start, freedom from this world’s madness and its corrupt systems. That promise is for you, wherever you are in your life, whatever you struggle with and whatever your level of understanding. You may have had it claimed for you when you were an infant but you can and should continue to claim that promise daily. That is how the promises of God always work.